North Carolina’s higher education market is, for the most part, vibrant. The state is home to more than 50 four-year universities as well as 60 community colleges. And online education, certificate programs, and non-traditional job training initiatives have given prospective students even more options. Nevertheless, some institutions are experiencing significant financial woes. Unaddressed, such problems could result in campus closings or, worse, perpetual taxpayer bailouts of ineptly-managed universities.

In recent years, what’s happened nationally has also happened in the Tar Heel State. That is, higher education has been challenged by two major stressors: increased competition from non-traditional education providers and lackluster enrollment growth (and in some instances, steep enrollment declines). The schools most affected by these trends have been small, tuition-dependent private colleges and historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs).

One way to gauge whether colleges and universities can meet their financial obligations and remain competitive is to examine their credit ratings. In January 2015, Moody’s Investors Service—which analyzes the finances of nearly all of the nation’s 4,495 Title IV degree-granting universities—reported that the outlook for U.S. higher education is poor. The agency cited several key drivers of instability in university finances, including slow revenue growth, mounting expenses, and students’ increasing tuition price sensitivity. In some states, declining higher education appropriations have contributed to the volatility.

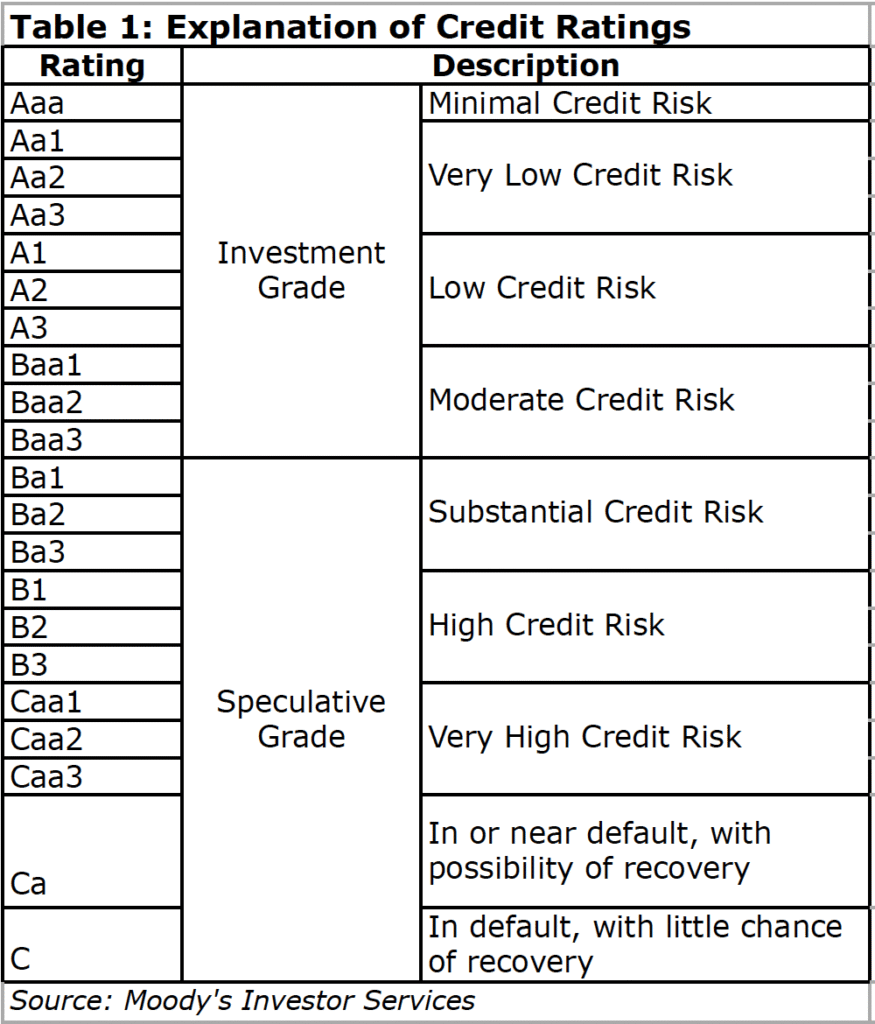

Moody’s reported that the median rating for public universities was A1 in January 2015. The median rating for private universities was A3. (See table 1 for an explanation of Moody’s ratings.)

Standard & Poor’s, another credit rating agency, has reached similar conclusions. Its senior director predicts that declining enrollment across the U.S. could negatively impact some schools’ credit ratings—particularly those of for-profit institutions and colleges in states with declining populations. One of the agency’s recent reports states, “rising college costs—both from tuition and other expenses—could begin to significantly stress the ratings on some schools and universities, particularly those in highly competitive markets.”

Standard & Poor’s, another credit rating agency, has reached similar conclusions. Its senior director predicts that declining enrollment across the U.S. could negatively impact some schools’ credit ratings—particularly those of for-profit institutions and colleges in states with declining populations. One of the agency’s recent reports states, “rising college costs—both from tuition and other expenses—could begin to significantly stress the ratings on some schools and universities, particularly those in highly competitive markets.”

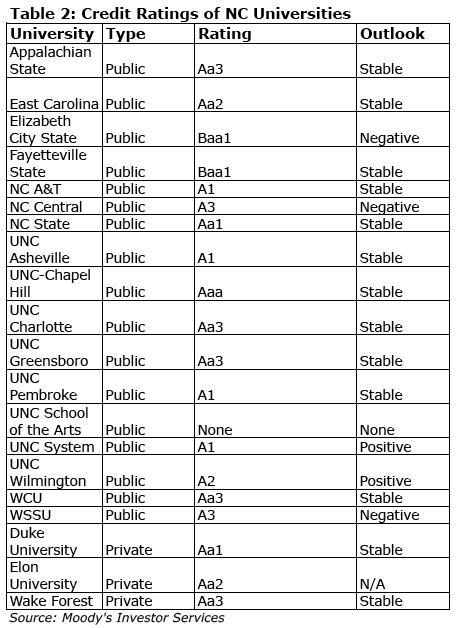

The Pope Center recently examined one such “highly competitive market”—that of North Carolina. Most of the schools that we were able to analyze (see table 2; many schools’ ratings were unavailable) have excellent credit ratings and a stable outlook for the future. For instance, UNC-Chapel Hill is one of only seven American universities that have a Moody’s rating of Aaa, which signifies the highest level of financial strength and lowest credit risk.

Unfortunately, in keeping with the national trend, a few North Carolina universities are showing signs of instability. In particular, some of the state’s historically black universities appear to be in dire financial straits.

In August 2015, Moody’s revised North Carolina Central University’s outlook from stable to negative. (A negative outlook means that a downgrade is possible if the university is unable to improve performance.) Moody’s reported:

The negative outlook reflects potential challenges in restoring fiscal stability in the near term as FY 2016 will likely be the fifth year of overall declines in revenue. While the university has demonstrated its ability to constrain expense growth, operations and debt service coverage will remain thin for the next several years. Further declines in already modest cash flow and liquidity would result in rating pressure.

The credit rating agency said that by strengthening student demand, enhancing operating performance, and increasing liquidity and financial resources, NCCU could boost its rating in the future.

Elizabeth City State University, another one of the state’s five public HBCUs, also shows signs of weakness. Moody’s recently downgraded the university’s fixed rate general revenue bonds to Baa1 from A3. The service noted that the schools’s outlook is negative due to “expectations of continued student demand challenges, which could lead to operating performance pressures.”

In some cases, it is state funding alone that has prevented Moody’s from significantly downgrading UNC system schools’ credit ratings. For example, after the agency downgraded Winston-Salem State University’s outlook to negative in 2014, it declared, “[the] rating is supported by the university’s membership in and the oversight from the University of North Carolina System; [and] strong state support for operations and capital from Aaa-rated state of North Carolina.”

Going forward, unless these troubled public universities take significant steps to improve their financial stability, it’s likely that the state’s taxpayers will be on the hook for an indefinite bailout. It’s also likely that there will be a series of short-term “fixes” that compromise educational excellence. (One such compromise came in October 2014 when the UNC system’s Board of Governors voted to allow three HBCUs with falling enrollment to admit students with SAT scores and high school GPAs below the system minimum.)

Fortunately, there is another path. It’s one that, if followed, could bring about the financial turnaround that these universities desperately need. That path has been paved by some of North Carolina’s private universities. Institutions such as William Peace University, Saint Augustine’s University, and Belmont Abbey College have found innovative ways to weather recent economic downturns.

By cutting administrative costs, downsizing faculty and staff, and strategically expanding degree offerings in high-enrollment disciplines (or cutting low-enrollment programs), such private schools have offered a clear and welcome alternative to what has happened at some of the state’s HBCUs. What’s unclear, however, is whether state policymakers will have the courage to demand similar changes if university leaders fail to act.

In any event, it’s obvious that a university’s financial strength—or lack thereof—impacts its ability to cover operating costs such as faculty salaries, maintenance, dormitories, libraries, and athletics. In this swiftly changing higher education environment, poor credit ratings could be a sign of big changes to come. Just how big those changes will be will depend on whether universities choose to be proactive or complacent.