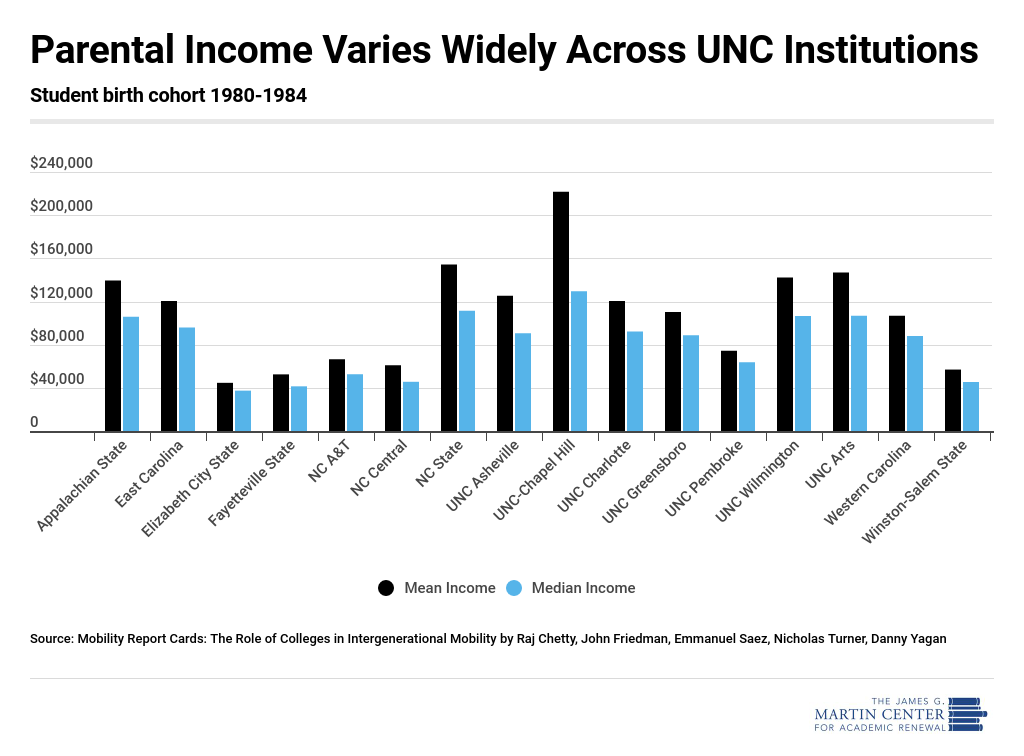

The University of North Carolina system boasts a diverse set of institutions. There are many ways in which the 16 schools differ: size, geography, research intensity, curriculum, and student characteristics. They also differ in terms of students’ family income.

As part of the Opportunity Insights project at Harvard University, Raj Chetty and a team of researchers collected data about social mobility at the nation’s colleges and universities. They describe the data:

We calculate college-level values as means over students in the 1980, 1981 and 1982 birth cohorts. When data for a college from any of these cohorts are incomplete, we use data from 1983 and 1984 cohorts to obtain an estimate.

That means that these data come from students who began college roughly 20 years ago, between 1998 and 2002. While there’s reason to believe that some change has occurred since then, parental income still varies considerably between institutions. Percentages of students receiving Pell grants at each school in 2017-2018 reveal that the number of low-income students is much higher at the state’s historically black colleges and universities than at its predominantly white institutions. Across the board, more students received Pell grants in 2017-2018 than in 2008-2009 (the first year for which Department of Education data are available).

Since student need is based on cost of attendance and expected family contributions, that increase in Pell grant recipients could be attributed to either schools accepting more low-income students or the increasing costs of college. Or perhaps to both.

“Mobility Report Cards: The Role of Colleges in Intergenerational Mobility” by Chetty, et al fully explains the data at a national level. It can be downloaded here.

Jenna A. Robinson is president of the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal.