Over the last several years, a burgeoning new genre has put the book-watching world on notice. “New Adult,” a coinage first used by St. Martin’s Press in 2009, refers to novels with greater depth than standard YA fare but far less than traditional literary fiction. Intended for twentysomethings unready for the challenge of real books, the New Adult category spans romance, fantasy/horror, and drama while asking little of its readers beyond cursory attention and a seated posture. Its sales, needless to say, are superb. Yet it just might represent a kind of national intellectual apocalypse.

Profiled by Buzzfeed, Book Riot, and The Daily Fandom in the last 12 months alone, New Adult novels are so precisely aligned with the Millennial-and-younger zeitgeist that one half expects individual tomes to begin placing orders on Uber Eats. Protagonists are stunted, hypersensitive, or otherwise fashionably damaged. As often as not, they spend their leisure hours taking exacting measure of their physical and mental health.

Gen-Z clichés notwithstanding, New Adult novels are perhaps most notable for their horrendous prose. Consider, for example, the main character of Lycanthropy and Other Chronic Illnesses, one of eleven New Adult titles celebrated in a 2021 article on ThriftBooks. A sufferer from chronic Lyme disease, Priya disenrolls from Stanford, moves back in with her parents, and joins a virtual support group on the social-media platform Discord. Nearly besting Priya for sheer triteness of design is the central figure of The Seat Filler, a dog-groomer with a “pathological fear of kissing” and a history of panic attacks.

Gen-Z clichés notwithstanding, New Adult novels are perhaps most notable for their horrendous prose. Take, for instance, the following paragraph from Kiley Reid’s Such a Fun Age, selected nearly at random but representative of the quality of the writing throughout:

Emira watched Mrs. Chamberlain’s face go into the same warfare that her daughter’s did when schedule did not go according to plan [sic], or when Emira tried to read to her at night. With her hand on the door, Mrs. Chamberlain seemed to brace herself as if she were preparing to be hit, or as if she already had been and barely made it out alive.

Leaving aside the curious imprecision of the final image—how, exactly, did Mrs. Chamberlain brace herself?—Reid’s sentences are simply awful as units of descriptive prose. What does it mean for a face to “go into … warfare”? Why does the word “schedule” lack an indefinite or limiting article (“a” or “the”)? To be clear, Kiley Reid is almost certainly a talent, having attended the famed Iowa Writers’ Workshop and contributed to the high-end literary journal Ploughshares. That she is writing badly here feels like a compositional feature: one facet of a bargain in which the author pledges not to overtax the reader’s mind.

Something similar may be operative in Raven Leilani’s debut, Luster, a New York Times notable book of the year (2020) and a finalist for the prestigious PEN/Hemingway Award. Despite its many accolades, Luster is so poorly styled that one wonders if the author intentionally dumbed it down. Here, again, a sample:

The next morning Eric texts me, three days. not even going to guess what it is? I don’t respond because I would like to avoid the awkwardness of upstaging whatever the surprise actually is, and because the tenor of this question, his unsubtle displeasure at my lack of response, is a moment I want to savor.

Criminy, does no one edit this stuff?! Beneath the achingly clunky prose, close-by the unnuanced emoting, lies a gender dynamic that manages to be at once stereotypical and confusing. Yet here, too, we have an author from a storied MFA program (NYU, which I also attended), whose magazine credits (The Yale Review and Granta) are excellent.

It betokens something puzzling when exquisitely trained fiction writers launch their careers with obvious dreck. Though the term is probably outré in this age of micro-aggressions, Reid, Leilani, and other New Adult novelists are clearly slumming. To write for a lowbrow audience is no crime, of course, but it does betoken something puzzling when exquisitely trained fiction writers launch their careers with such obvious dreck.

As for the identity of that “something,” the careful reader will have already guessed. Market forces, much despised by literary types, are nevertheless the guiding factor in publishing as in other industries. If the people want flat characters and artless prose, by God, they shall have them. The only question is why they should desire those things in the first place.

To address that mystery, it is necessary first to consider who is doing the book-buying in this country. According to March findings from the Survey Center on American Life, 50 percent of college-educated women and 40 percent of college-educated men report having read a book in the past week. For non-college-educated Americans, the percentages drop to 34 and 15, respectively.

Pursuing a similar query in September of last year, the Pew Research Center found that “adults with a high-school diploma or less are far more likely than those with a bachelor’s or advanced degree to report not reading books in any format in the past year (39 percent vs. 11 percent).” Plainly, and as one would expect, America’s leisure readers are those men and women who have completed a formal university education and whose tastes—this is, of course, crucial—have been duly shaped by the experience.

What, then, are they learning at school? Or, to shape the question to our particular concerns, what are they learning to value?

Widely noted in conservative and mainstream outlets has been the recent tendency of English faculty to jettison the canon in favor of a more voguish curriculum. Having shunted aside Shakespeare, literature profs are free to wallow in High Theory (e.g., “post-structuralism”) and assign books that give voice to current race and gender obsessions. Lest the reader object that what happens in obscure departments is unlikely to affect whole student bodies, allow me to make the connection explicit. If an English teacher will not give canonical texts to majors, he is highly unlikely to bring them into general-education Freshman Lit. I say this as a 15-year veteran of the college English classroom.

Having been taught nothing better, today’s readers have no sense of what they’re missing and are instead satisfied with pap. The game is given away by the requirements of “Common Read” programs, in which universities ask all incoming freshmen (or all students) to peruse a single text. In October 2020, Penguin Random House compiled a spreadsheet of 470 such programs and their selections. Careful examination of the list reveals a mere three titles that could reasonably be described as classics (The Call of the Wild, Plato’s Meno, and Frankenstein). The following year’s list, covering 460 programs, turns up a mere seven.

By contrast, Ibram X. Kendi’s How To Be an Anti-Racist and Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me together take up a startling 40 slots over the two-year period. Just Mercy, the Bryan Stevenson memoir turned Michael B. Jordan flick, was assigned by a whopping 16 universities in fall 2020 alone.

It should, at this point, be conceded that Stevenson, Coates, and (especially) Kendi are important writers. It is not unreasonable to ask students to grapple with their ideas. The problem is not that these faddish books are political but that they are crowding out works of world-historical significance, or even essential contemporary authors like Cormac McCarthy and Tobias Wolf. Never mind that Kendi and his fellow race-baiters are advancing a counterfeit ideology. To teach them in place of the greats is itself a damaging ideological choice.

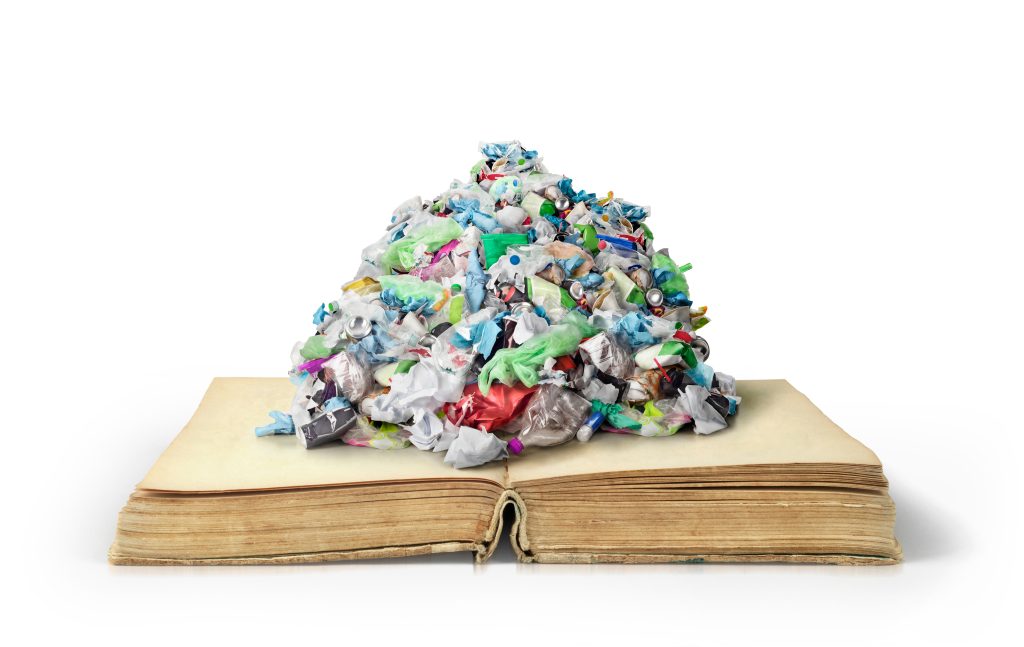

Given these circumstances, it is not difficult to explain the popularity of New Adult fiction. Having been taught nothing better, today’s readers have no sense of what they’re missing and are instead satisfied with pap. Meanwhile, whole libraries of near-miraculous literature sit untouched, gathering dust. If we wish, we can reach out and grasp them once again.

Will we?

Graham Hillard is editor at the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal.