Jacob Rice, Unsplash

Jacob Rice, Unsplash College administrators and athletic departments, along with the media and much of the broader public, proclaim that college athletics are the “front porch” of the university. If athletics are a key component of a university’s prestige and brand, an attractive “front porch” enables a university to leverage the athletic program to its benefit by increasing enrollment, student quality, and donations. The house behind the front porch, like the front porch itself, will be attractive and well-built.

In a paper published in the Journal of NCAA Compliance (co-authored with Jerry K. Slice), we test the proposition that the “front porch” (athletics) is truly indicative of an institution’s overall quality, particularly the quality of its educational program. More directly, do universities with winning athletic programs rank high on metrics of academic and educational quality? And does it matter if the athletic program is well-run financially? The findings indicate that winning athletic programs and educational quality do go together but also that financially sound athletic programs and educational quality go together.

Do universities with winning athletic programs rank high on metrics of academic and educational quality? To test the link between athletic success and educational quality, we used data on 97 Football Bowl Subdivision teams from public institutions, for which we could get data on all variables of interest. For athletic success, we used ESPN’s Football Power Index (FPI) and ESPN’s Men’s Basketball Power Index (BPI), both of which measure “how many points above or below average a team is.” We took five years of data and calculated the average and standard deviation of the respective power indexes and then calculated the ratio of the average power index divided by the standard deviation of the power index for each team. These measures are better than simple FPIs or BPIs, because they add consistency to the measures of athletic performance, so that if two above- (or below-) average teams had the same average FPI or BPI, the team with less (or more) season-to-season variability in performance would have a higher (or lower) score. For educational quality, we used the Wall Street Journal/College Pulse Best College Rankings, which utilize three student-centered metrics—student outcomes, the learning environment, and diversity—with the goal of “measuring the value added by college—not simply measuring their students’ success, but focusing on the contribution the college makes to that success.”

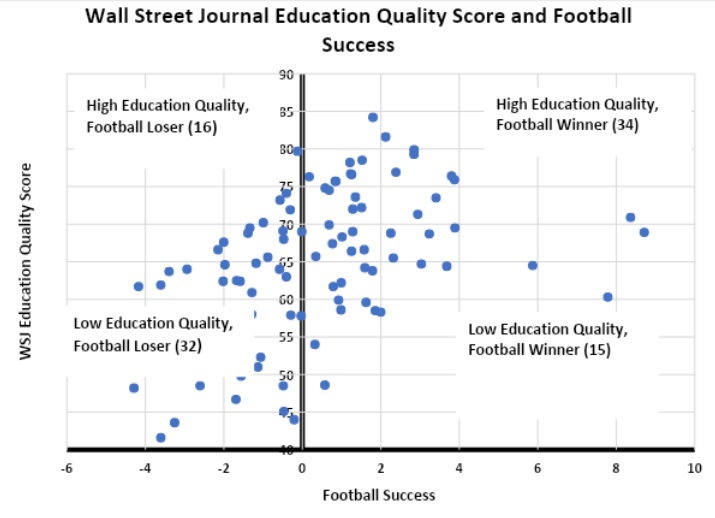

The figure below provides a scatterplot that breaks down the 97 institutions into quadrants of different levels of educational quality and football success. High or low educational quality is determined by being above or below the average WSJ score of 65, and being a football winner or loser is determined by being above or below the football success average of (nearly) zero. The number of schools in each quadrant is designated parenthetically. For 66 of the 97 schools, high educational quality is associated with a winning football program, or low educational quality is associated with a losing football program. Football success, or the lack thereof, is a good predictor of educational quality.

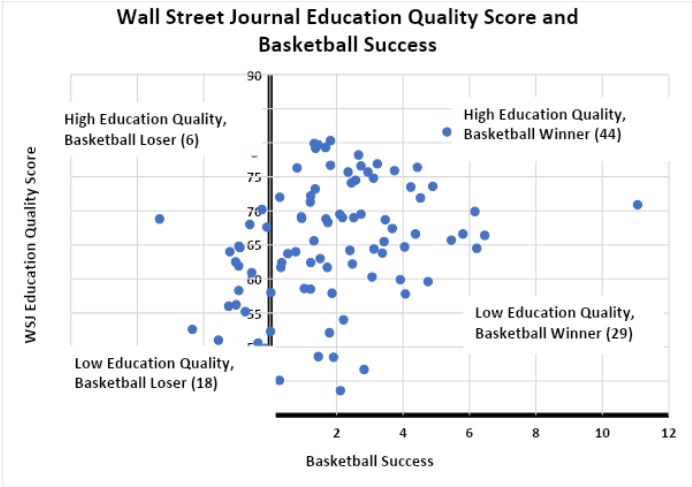

The next figure provides the same breakdown for educational quality and men’s basketball success. For 62 of the 97 schools, high educational quality is associated with a winning men’s basketball program, or low educational quality is associated with a losing men’s basketball program. Like football success, men’s basketball success, or the lack thereof, is a good predictor of educational quality.

These findings provide support for the idea that athletics are the “front porch” of the university. Athletic success indicates that the house behind the front porch, the educational program, is also likely to generate success for the institution’s students.

An institution with an athletic program that is self-supporting or nearly so is not diverting resources from the institution’s core educational mission. What should prospective students and their parents make of these findings? To reiterate, in most cases winning athletics are a signal of a high-quality educational program, and losing athletics are a signal of a low-quality educational program. Yet, as shown in the scatterplots, the correlations are not perfect: Some schools win on the field and court but offer low-quality educational programs, and other schools lose on the field and court but offer high-quality educational programs. There must be more to the story. As when buying a house, a close inspection is wise, for that which catches the eye may, at times, hide what is underneath the surface. An examination of how colleges finance their athletic programs provides students and their parents with a look underneath the surface.

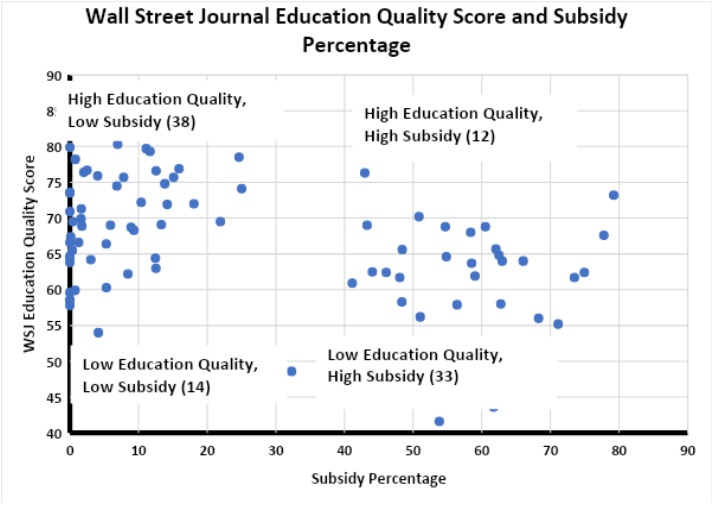

As a final investigation of the house behind the front porch, we used data from USA Today, which uses a methodology to determine the share of athletic revenues from the “sum of student fees, direct and indirect institutional support and state money allocated to the athletic department, minus certain funds the department transferred back to the school.” The following figure again breaks down the 97 institutions into quadrants, with the subsidy percentage of the athletic budget on the horizontal axis. For 71 of the 97 schools, high educational quality is associated with a low athletic subsidy, or low educational quality is associated with a high athletic subsidy. Institutions with athletic programs that have enough revenue to be self-sufficient, or nearly so, whether through ticket sales, television, bowl games, and donations or because the athletic program is right-sized, have more resources to support their core educational mission. On the other hand, institutions with athletic programs that siphon revenues from the broader institutional budget, whether through insufficient revenues generated or because their athletic program is wrong-sized (too big), have fewer resources to support their educational program.

The upshot of this analysis broadly supports the front-porch hypothesis, as typically stated by athletic departments and the media and as understood by the broader public: Winning athletic teams indicate that an institution is likely well-managed, with a quality educational program that benefits its students, and losing athletic teams indicate that an institution is likely poorly managed, with an educational program of marginal value for its students. But students, their parents, and other constituents of higher education would be wise to look beyond the win-loss record. An institution with an athletic program that is self-supporting or nearly so is not diverting resources from the institution’s core educational mission and is likely serving its students well. On the other hand, an institution with an administration and governing board that insist on maintaining an athletic program that requires a substantial draw of resources from the overall institutional budget is diverting resources from its educational mission and is likely serving its students poorly.

An attractive, appealing front porch likely indicates that the house behind the front door is also well constructed, functional, and perhaps immaculate, whereas a shabby front porch likely indicates that the house behind the front door is in a state of disrepair, too. But, in either case, and especially the former, the buyer would do well to inspect the house behind the front porch before buying. The same is true for buyers of higher education. Winning athletics often indicate that the house behind the front porch, the educational program, is of high quality, but students and their parents would do well to examine the educational program before buying. Buyer’s remorse feels bad, whether the purchase is a home or higher education.

Jody Lipford is associate professor of economics at Francis Marion University in Florence, South Carolina. He has published in Public Finance Review, the Independent Review, the Journal of Applied Sport Management, and Political Economy in the Carolinas.