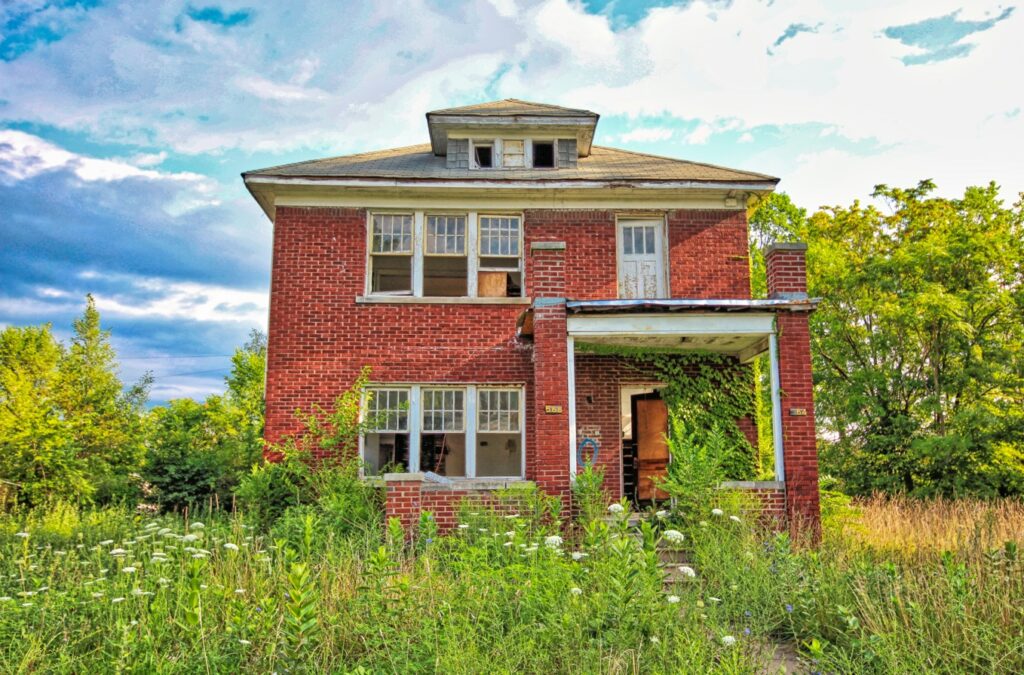

Daniel Tuttle, Unsplash

Daniel Tuttle, Unsplash You would think that the last thing colleges and universities need is more buildings—given declining enrollments, online classes, and changing attitudes about college. But that is not the way university leaders and their outside consultants see it.

Why? Many of their existing buildings are falling apart. Consider the following analyses:

- Gordian, a building-planning consultant, issued a report last year that describes a “13-year pattern of underinvestment in existing space” in colleges and universities. “Since the Great Recession there have been periods of increasing investment, but never at a rate that substantially reduces the gap between the target investment required to sustain existing building portfolios and the money made available.”

- Moody’s, a financial consulting firm, issued a report in August 2024, “Pent-up Capital Needs: The Hidden Liability with a Hefty Price Tag.” It said, “The large and growing backlog of capital need poses a significant credit risk for the higher education sector. […] Even large university systems that have consistently allocated significant resources toward capital investment are facing considerable levels of deferred maintenance.”

Deferred Maintenance Is the Culprit

Ah! Deferred maintenance—that is the culprit and the reason why these reports are so gloomy. Keeping buildings attractive, safe, and efficient costs money. If maintenance is done properly, no outsider even notices it. The invisibility of maintenance means that maintenance is often delayed. Funds are shifted to more obvious needs. Exactly how that happens isn’t clear: What is clear is that maintenance is being delayed in favor of more attractive spending priorities.

The invisibility of maintenance means that maintenance is often delayed. Yet deferred maintenance builds up, with unpleasant consequences.

In 1989, Edward V. Regan, at the time the comptroller of New York State, wrote an article for the Academy of Political Science, “Holding Government Officials Accountable for Infrastructure Maintenance.” Noting a series of major infrastructure failures, including a bridge collapse, a highway collapse, and “crumbling walls and leaky roofs in many New York City school buildings,” he offered a useful explanation for deferred maintenance, summarized here.

- Most cities, other governments, and long-term institutions have essentially two budgets: an annual budget and a capital budget. (This is also true of universities.) Maintenance expenses come from the annual budget, but new infrastructure is paid for by the capital budget. The capital budget is financed by bonds and other long-term debt. With new buildings, the annual budget pays only for interest on such debt. So once maintenance is deferred to the point where the building or bridge or highway collapses or must be replaced, “the cumulative cost of years of neglect is transferred from one generation to the next.”

- Furthermore, a new bridge (or school or highway) is a news event. A politician can boast about it, and there may even be a ribbon-cutting ceremony. It’s more expensive than proper maintenance would have been, but it gets more attention, almost always positive.

Organizations that don’t have to make a profit—such as governments—are more susceptible to deferring maintenance than are private profit-making companies. For a profit-making firm, the ultimate costs of deferred maintenance are potentially so high that they can make the difference between success and bankruptcy. So maintenance in private firms is rarely deferred.

In contrast, governments hardly ever go bankrupt, and non-profits rarely do.

In fact, Comptroller Regan pointed out that “deferred maintenance” (sometimes called DPR) has become a widely accepted term in many political circles. The term is “not even viewed as a pejorative,” wrote Regan; “it sounds like a government program!”

Organizations that don’t have to make a profit are more susceptible to deferring maintenance. UNC Facilities

Let’s look at the University of North Carolina System. The system keeps a careful watch on the state of its buildings and recently issued a report on their condition.

The news was not good, though. “The common practice of deferring standard maintenance of university facilities has forced many institutions to face the prospect of extensive renovations and the total replacement of some buildings.”

Making this problem worse—and even ironic—is the fact that many buildings currently in the system are underused. The university tracks the relationship between classroom and laboratory capacity and student usage. It sets a standard of 35 hours per week for classrooms and 20 hours per week for laboratories. That is, on average, campuses’ classrooms should be used for 35 hours a week and laboratory space for 20 hours a week.

No UNC campus is meeting that standard (as of 2022, the latest year for which numbers are available). The best utilization of classroom space is by NC State, at just over 30 hours per week; the best utilization of laboratory space is by UNC Wilmington, at slightly over 18 hours. The averages for all campuses are 22.6 hours (classrooms) and 13 hours (labs), well below the university target.

It’s troubling that, even though buildings are underused for key university requirements (classes and laboratory work), taxpayer dollars are being spent to build more of them.

Universities are far from alone in deferring maintenance. And solving the problem elsewhere, too, is elusive. Consider the National Park Service (NPS). Like universities, our national parks are considered a great American treasure. Yet NPS has fallen seriously—one might say spectacularly—behind in its effort to make park facilities safe, useful, and comfortable.

In 2020 Congress passed the Great American Outdoor Act. Among other things, it devoted a large amount of money—$1.53 billion a year for five years—to address the park service’s deferred maintenance. Tate Watkins, a research fellow with the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC), has just prepared a report on its progress.

We should not let underused but functional buildings rot in order to build shiny but also underused new ones. “Funding from the Great American Outdoors Act may be on its way to improving thousands of federal assets, but the picture has been muddled by a maintenance backlog that continues to grow,” Watkins writes.

Grow, not shrink? When the law was passed, the agency’s estimated maintenance backlog was $14.9 billion. But four years into the remedial work, the backlog has soared to $23.7 billion! Not only does that figure discourage the congressmen who supported the law, but it also illustrates the problems with identifying and preventing deferred maintenance.

The same dilemma besets universities.

Hope for catching up on maintenance is not great; yet there may be some motivation. As Moody’s points out, the quality of the campus is a key factor in attracting students. In today’s environment, colleges are avidly competing for students. Writes Moody’s: “Colleges and universities that are unable to offer updated facilities, advanced technology and an attractive physical environment risk losing competitive standing.”

That message might be heard but ought not to be misinterpreted. We should not let underused but functional buildings rot in order to build shiny but also underused new ones. Yet the pressures to spend money on immediate and visible issues rather than to stem creeping deterioration are strong. Incentives need to change.

Jane S. Shaw (who also writes under the name Jane Shaw Stroup) was president of the John W. Pope Center for Higher Education Policy (now the Martin Center for Academic Renewal) until February 2015, when she retired and joined the center’s board of directors. She is now chairperson of the Martin Center’s board.