More money flows to arenas and building upgrades. The hunt for recruits gets more competitive. University presidents brag about how their new program will make the school nationally known.

But the cause isn’t basketball or football.

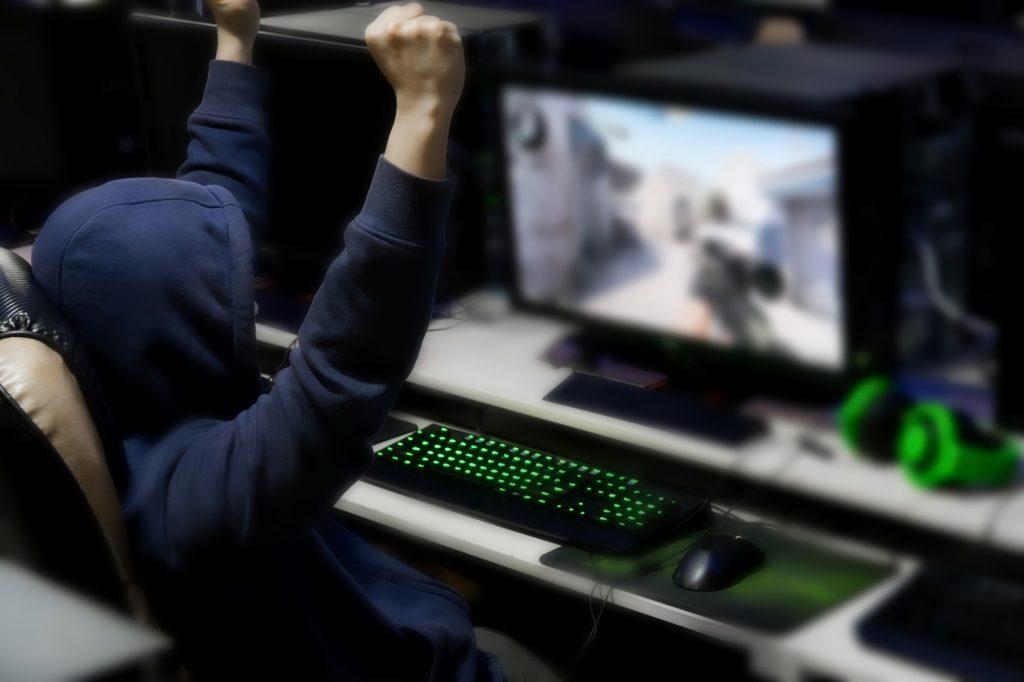

This time around, the athletics arms race on campus is for “esports”—competitive video gaming. And it’s a trend driven by many small colleges hunting for students.

Though new, esports are not a niche. Within only a few years, they have gone from small, student-driven clubs to official extensions of the university. So far, 126 colleges have joined the National Association of Collegiate Esports (NACE), a governing body for varsity-level competitions. Student-athletes play games such as League of Legends, Overwatch, Rocket League, and Counter-Strike. Games are usually team-based and can be fighting, sports, fantasy, and strategy games.

NACE membership is rapidly growing, too. Michael Brooks, NACE’s executive director, told the Martin Center that they receive six or seven inquiries every day from schools wanting to join NACE. In a year, he estimated that NACE will have 300 affiliated schools and 800 schools within five years—though NACE tends to underestimate its growth.

Esports, it seems, is here to stay.

An esports program gives colleges a branding opportunity and students a reason to choose a specific college. “That’s the first issue, recruitment and retention of new students. The second thing is definitely branding. It’s harder for smaller institutions…to really build up that brand,” Brooks said.

So, students get a new sport to play or watch, colleges have another program to advertise, and few administrators stand athwart history, trying to stop higher ed’s growth into an entertainment juggernaut.

But branding doesn’t come cheap. Compared with traditional sports, esports costs are low. “The average startup cost is $43,000. There’s not a single sport within traditional sports that even comes close to that low level of entry,” Brooks said. However, as press releases from colleges attest, their “state of the art” esports arenas, IT infrastructure upgrades, and other spending can quickly surpass a modest investment.

The University of Akron, for example, will spend more than $1.2 million for esports facilities, operating costs, and other expenses, according to The Chronicle of Higher Education. Their 2019 esports budget is almost $500,000. Sponsorships could cover some expenses, but attracting them will take years. The four sponsorships for Akron’s esports team, according to public records obtained by the Martin Center, only cover a cashback deal on computer purchases, team apparel, audio accessories such as headsets, and a $5,000 donation for a scholarship fund.

After Akron’s recent success in conference and national competitions, officials expect more deals. “We have seen significantly more progression in fundraising over the past few months,” said Michael Fay, the head coach and director of Akron esports. They also want to develop other revenue sources such as running summer camps, gaming conventions, and selling community passes for the use of gaming stations.

“Most programs are going to monetize based off of student participation, sponsorships, alumni support, boosters, and donations…a heavy reliance on sponsors and alumni support,” Brooks said.

Another revenue source is tournament winnings. NACE-run competitions sometimes have prize pools up to $50,000, and collegiate competitions run by video game developers Riot Games and Blizzard Entertainment can exceed that. Prize pools, though, vary greatly and are lower in collegiate competition than professional competition. However, most prize-winnings are for student scholarships and educational expenses, not program costs.

Broadcasting competitions, too, could generate funding. “The esports industry has yet to actualize the full financial potential from live-streaming tournaments,” Thomas Baker of the University of Georgia and John Holden of Oklahoma State University argued in the South Carolina Law Review. Though professional esports have a larger audience, industry experts told Baker and Holden that college programs have “the potential to be a significant revenue generator for schools.”

Like other sports, though, unsuccessful teams will struggle to generate revenue. Not every million-dollar program can break even.

And Akron’s chances at success may be better than most NACE schools. Many NACE-affiliated schools are small, regional liberal arts colleges. Delaware Valley University, Catawba College, and Northwest Christian University easily outnumber larger schools like the University of North Texas, Boise State University, and the University of Missouri.

Those smaller schools have seen enrollments fall and are trying to find new ways to bring in students. “Smaller named institutions…are always looking for different programming, really anything that can attract students, that can put them on the radar of a potential student,” Brooks said. After early adopters got national attention and student enrollments specifically for their esports programs, it was “a little bit off to the races,” he said.

And that success in using esports as a recruiting program has been repeated at other schools. A 2017 study in the Journal of Intercollegiate Sport interviewed more than 30 gamers at one college and found that a majority of them enrolled due to esports. “The potential reward for recruiting/branding is absolutely immense,” Brooks said.

Smaller schools have seen enrollments fall and are trying to find new ways to bring in students.Esports isn’t only for attracting students, either, its supporters say. They offer benefits similar to traditional sports. For instance, students learn teamwork and communication, develop discipline, and stress control. Also like traditional sports, colleges use their esports programs to train students in areas such as management and event planning, marketing, and business development.

It also has some advantages that traditional sports don’t.

“The No. 1 thing is inclusivity,” said Gidd Sasser, the coordinator of esports and head coach at Catawba College in North Carolina. “This is the one sport where anybody can play. Anybody with mental, physical disabilities or who do not traditionally fall under the football/basketball [athlete type] can compete at a high level.”

Founded in October 2018, Sasser said the Catawba program signed 12 student-athletes for the spring semester, all transfers. For the fall semester, he is vetting about 50 incoming freshmen. Catawba isn’t treating esports as a flash-in-the-pan fad, either. “The school had been thinking about this for a long time,” Sasser said. “This isn’t something that’s not just, ‘let’s do it for money.’ This is something we want to invest in…they’re looking at this as a long-term investment just like football and basketball.” Michael Fay at Akron expressed similar sentiments.

Catawba is the only North Carolina school to have a varsity (rather than club) esports program and houses it under student affairs, not athletics. That arrangement is common, as many programs place esports under student affairs. Others, like the University of Akron, put it under an honors college or, like the University of Utah, under an engineering school. Generally, esports programs get incorporated wherever the interest comes from, Brooks said. About 47 percent of NACE schools have esports under student affairs and another 40 percent have them under athletics, according to Inside Higher Ed.

One difference in esports is that they won’t become a de facto minor league for professional esports like football and basketball. Professional esports players tend to delay college rather than use it as a training ground. “It is more probable that degree attainment would be the primary objective for most collegiate esports players who rely on varsity scholarships to pay for their education,” Baker and Holden noted in their law review article.

“Esports is not so different as adding a new activity or a new sport onto campus. The only reason it’s a little bit different than most is because it has such a spotlight on it right now and it’s growing at such a fast rate,” Brooks said.

This new activity has succeeded in attracting students. Giving up a proven tool at a time when many small colleges struggle to avoid enrollment declines is a hard case to make to college presidents. Unless university governing boards, alumni groups, or the public ask tough questions about the long-term wisdom of esports programs, they will become another part of campus culture—and another budget line item.

Anthony Hennen is writer/editor at the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal.