Adam Nir, Unsplash

Adam Nir, Unsplash Legal battles over President Biden’s various schemes to forgive student debt continue. In July, the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals indefinitely blocked the administration’s ultra-generous new student-loan repayment plan, which could have cost taxpayers $475 billion. Additional loan-cancelation initiatives—also certain to face legal challenges—are in the works.

But the high drama of loan cancelation has drawn attention away from a more pressing issue in the student-loan system. After the pandemic-induced student-loan payment pause ended last year, the Education Department implemented a one-year transition period to allow borrowers time to ease back into the habit of paying their loans. That so-called on-ramp is set to expire at the end of September—yet tens of millions of borrowers have not yet made a payment.

The federal repayment “on-ramp” is set to expire at the end of September, yet tens of millions of borrowers have not yet made a payment. The Looming Student-Loan Nonpayment Crisis

During the payment pause, no federal student-loan borrower had to make a payment, and interest rates were set at zero. During the on-ramp, payments are due and interest accrues once again. But borrowers who don’t pay their loans can avoid the worst consequences of failing to do so: Delinquencies will not appear on their credit records, nor will loans be placed in default or sent to collections.

Since most student borrowers had not made a payment on their loans for over three years, the logic of a one-year on-ramp was to allow borrowers time to make financial arrangements to recommence payment. Missing a payment or two would be no big deal. After a year, the logic ran, most borrowers should be comfortably paying their loans every month.

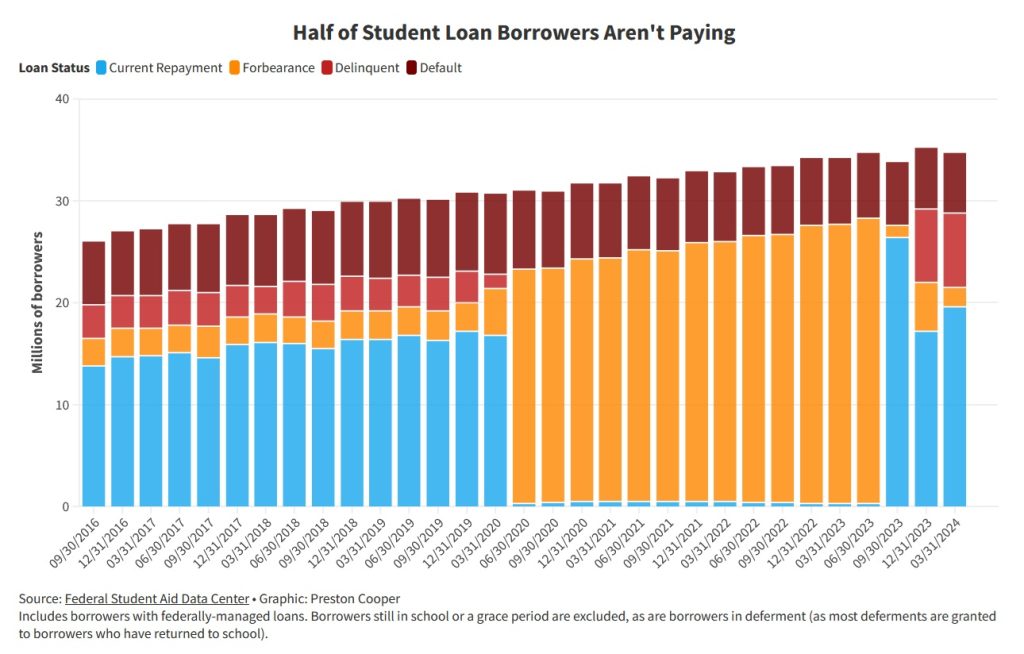

That ideal couldn’t be farther from reality. At the end of 2019, prior to the payment pause, 3.1 million borrowers were more than 30 days behind on their loan payments. As of March 2024—the latest month for which data are available—the number of delinquent borrowers had reached 7.3 million.

Another feature of the post-pause transition was a program to allow borrowers who had been in default prior to the pandemic a one-time chance to bring their loans back into good standing. Yet most defaulted borrowers have not availed themselves of this option. In December 2019, 7.7 million borrowers were in default; as of March 2024, the ranks of defaulted borrowers stood at 5.9 million.

Other borrowers are taking advantage of legitimate options to avoid paying their loans. As of March 2024, two million borrowers had entered loan forbearance, a status in which payments are not due.

The number of borrowers not paying their loans exceeds 20 million. Many more borrowers are enrolled in an income-driven repayment (IDR) plan, which allows them to pay less than the standard monthly amount—and sometimes nothing at all. The most popular IDR plan is the SAVE plan, a creation of the Biden administration that allows borrowers with even relatively high household incomes to qualify for $0 monthly payments. As of February 2024, 57 percent of the 8 million borrowers enrolled in the SAVE plan paid nothing towards their loans each month. (While the SAVE plan is currently on hold due to legal challenges, the Biden administration has placed all SAVE borrowers into interest-free forbearance while the court battle plays out.)

Add the 15 million borrowers who are delinquent or in default on their loans to the two million borrowers in forbearance and the four million who paid nothing under the SAVE plan, and the number of borrowers not paying their loans exceeds 20 million. Excluding those enrolled in school, there are around 35 million borrowers total. That means more than half of student borrowers who should be paying their loans are not.

What Happens to Borrowers Once the On-Ramp Ends?

All this is costly for taxpayers. It’s one reason the Congressional Budget Office expects the student-loan program to post a loss of $400 billion over the coming decade. But the nonpayment phenomenon also carries major implications for borrowers.

Think about the last few years from the perspective of a student borrower who doesn’t religiously follow the news. You’re allowed to make no payments on your loans for three and a half years, from the beginning of the pandemic until October 2023. During that time, you hear that student-loan forgiveness is coming. After October, your servicer starts sending you bills again, but you face no real consequences for missing your payments month after month. All the while, you continue to hear more promises from the president and media about loan cancelation.

It’s understandable that a borrower in this situation might assume that he can get away with not paying his loans forever—or at least until one of those loan-forgiveness promises comes true.

But things are destined to change after the on-ramp expires in October. First, loan delinquencies will be reported to credit bureaus, which generally happens when payments are 90 days overdue. That will adversely affect borrowers’ credit scores.

The Education Department has the power to garnish wages, withhold tax refunds, and seize Social Security checks. A borrower who goes nine months without making a payment will enter default. After that, the Education Department will have the power to garnish the borrower’s wages, withhold his tax refund, or seize his Social Security checks. Defaulted borrowers can also be responsible for enormous collection fees.

Even borrowers on an IDR plan may not be out of the woods. Recent research has found that borrowers who qualify for a $0 monthly payment often become disengaged from the student-loan system and neglect to reapply for IDR each year. This can lead to higher rates of student-loan delinquency in the long run.

The Biden Administration’s Plans for Student-Loan Repayment

Facing a potential nonpayment crisis in October, the Biden administration could opt to kick the can down the road by extending the on-ramp period. This may be the most likely outcome, as it makes the nonpayment crisis the next administration’s problem. But extending the on-ramp is not sustainable in the long run, as it means tens of millions of borrowers will continue to skip their payments—leaving taxpayers to pick up the cost.

Of course, many decisionmakers in the Biden administration are ideologically opposed to collecting the loans at all, so they may be fine with that. In the meantime, they will keep trying to forgive the loans outright. Though the administration’s highest-profile forgiveness plans are on thin legal ice, there are other ways to discharge debts. The Education Department has canceled $170 billion so far by bending the rules on other loan-forgiveness programs.

In addition, the administration has announced new proposals to forgive student debt by executive action. One proposal, announced in May, would forgive around $150 billion for 28 million borrowers. Another scheme, expected in October, could be even more consequential. These plans are still working their way through the regulatory process, but the White House has signaled it hopes to begin canceling debt this way before the November election.

Perhaps the administration will give up on actually collecting the loans in the hope that one of these forgiveness plans will survive legal scrutiny. Or perhaps officials figure that allowing the loan program to descend into chaos will leave no option but mass forgiveness. Either way, advocates of fiscal responsibility need to offer a better way forward.

A more responsible approach would send a clear signal that borrowers are expected to repay their loans. What Should We Do Instead?

A more responsible approach would send a clear signal that borrowers are expected to repay their loans. The on-ramp should end in October, as promised. Government officials should stop talking about mass loan cancelation to demolish any hint that borrowers should hold out for it.

There should be reforms to the repayment system, as well. A responsible policy would reverse the SAVE plan and institute a minimum monthly payment in remaining IDR plans, so borrowers remember they have a loan to repay. Long-term loan forbearance should no longer be an option, except in extreme cases.

But the government should meet borrowers halfway. Policymakers should make penalties for default less punitive and create simple pathways for defaulted borrowers to return their loans into good standing. Interest subsidies for lower-income borrowers who make a good-faith effort to repay their loans, as House Republicans recently proposed, would ensure borrowers can pay down their principal balances and eventually get out of debt.

Beyond changes to repayment, more fundamental reforms to student loans are necessary to prevent such a crisis from happening again. Congress should implement lower limits on student borrowing and require colleges to cosign the loans they foist on students. Privatization of the federal student-loan system (or at least portions of it) is also worth considering, as private lenders will make an apter assessment of prospective borrowers’ capacity to repay than does the federal government.

The political and legal wars over student-loan forgiveness are likely to stretch years into the future. By contrast, the end of the repayment on-ramp is an issue that demands attention today. More than 20 million student borrowers are not paying their loans, and the nation is about to discover what that means.

Preston Cooper is a higher-education policy expert based in Washington, DC.