Parradee, Adobe Stock Images

Parradee, Adobe Stock Images Artificial intelligence has democratized knowledge more than any invention in history. Anyone can now solve a problem in physics, medicine, or Greek literature instantly. Yet the safeguards that once verified a student’s mastery of a subject have been replaced by compliance rituals that only simulate it. Consider the following:

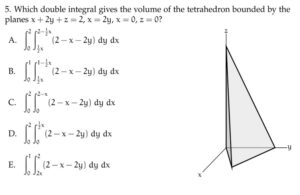

If you are using Google Chrome, Google Lens can now search images directly from your browser. Highlight the problem above, and within seconds a detailed, step-by-step solution appears. Try it yourself. What once required thought, practice, and time now takes a single click. That isn’t evolution; it’s a breakthrough, disruptive technology doing what it is meant to do: collapsing the distance between skill and result. In higher education, this transformative technology has created a perfect storm where tools that make cheating effortless have collided with an archaic compliance system that guarantees students get away with it.

Distance-education courses are eligible for Title IV aid only if they demonstrate “regular and substantive interaction.” Financial markets are pouring trillions of dollars into artificial-intelligence infrastructures, expecting nothing less than the greatest economic expansion in human history. AI won’t replace human effort; it will amplify it. A fivefold jump in knowledge-work productivity isn’t a fantasy; it should be the standard. Yet higher education, whose output makes that productivity possible, has been caught flatfooted, and the result is system dysfunction. The promise of AI rests not on faster chips but on stronger minds. Debating access, equity, grade inflation, or free expression while students cheat their way to a degree is like planning the breakfast menu on the Titanic.

Without clear federal guidance, schools have improvised. The road to hell is paved with good intentions. Through the Higher Education Act of 1965, Congress set out to protect Title IV funds from the supposed scourge of correspondence courses. In truth, correspondence learning made up only a small share of higher education. I even took such a class as an undergraduate, a political-science course that meant reading a textbook and sitting for two proctored exams at a testing center. Abraham Lincoln studied law the same way, by correspondence, and his assessment was the Illinois bar exam. With amendments in 1992, 1998, and 2008, Congress drew a line. Correspondence courses were ineligible for Title IV aid, and distance-education courses were eligible only if they demonstrated “regular and substantive interaction” (RSI), a term written into law but never clearly defined.

Without clear federal guidance, schools improvised. Department of Education inspector-general audits of the Western Association of Schools and Colleges (2016) and Western Governors University (2017) became de facto precedents. In the vacuum, colleges hired an army of compliance staff who spoke with the confidence of regulators but possessed the insight of mere bystanders, issuing mandates they barely understood, divorced from curricula or pedagogy. The Ohio State University and the University of Michigan, fierce rivals on the gridiron, landed on nearly identical RSI policies. Professors are held responsible for demonstrating course RSI, but the institution bears the risk of losing Title IV eligibility, having to repay federal funds, or even facing accreditation jeopardy if a randomly selected course is found deficient. Evidence of RSI must appear in an online course “shell,” yet it is rarely reviewed by anyone with real curricular expertise. In practice, RSI has little to do with teaching or learning. It produces syllabi that swell each semester with new disclosures and weekly online discussion boards meant to signal activity rather than foster understanding. I have even been told to add polls to online classes such as “What is your favorite study snack?” This is pencil-whipping disguised as pedagogy.

There is a lot at stake. Fear of losing aid drives institutions to over-engineer online course design, and the result is predictable: professors buried in learning-management-system (LMS) shells, performing compliance theatre instead of teaching. Each online course ends up looking like a custom software installation cobbled together by a dozen people who never met. They are brittle, prone to breaking, and demand endless tinkering: updating links, reformatting fonts, fixing bullet points that somehow pass muster one semester and get flagged the next. Compliance reviews depend less on standards than on whoever happens to be checking that week. The same course can be praised one term and rejected the next, depending on the reviewer’s interpretation or mood. Faculty teaching online have been conscripted into the role of instructional designer, a job few enjoy and even fewer do well.

Online learning has grown rapidly over the past two decades. Students now expect distance options, and, for professors buried in compliance minutia and course-design busywork, prepackaged publisher content offers an easy escape. What online students get are polished systems with canned lectures and auto-graded quizzes in a thin LMS wrapper: efficient for faculty but fatally flawed. These homework platforms look professional, yet they cannot guarantee academic authenticity, as the demonstration above shows. Faced with a choice between a section built on publisher content—where a week’s work can be finished in 15 minutes for an easy A—or a rigorous class that requires hours of study with no certainty of passing, students make the predictable choice. Rigor fades while the easiest online sections fill first. Increasingly, colleges no longer offer a genuine choice between traditional and online instruction. The system has standardized around convenience, not learning.

What online students get are polished systems with canned lectures and auto-graded quizzes. What began as a legislative fix to fence off correspondence courses from Title IV aid—a chain-link barrier meant to keep the neighbor’s dog out—has mutated into the higher-education equivalent of the Maginot Line. As the defenses for RSI compliance multiply, students increasingly sidestep the one safeguard that still ensures authenticity: proctored exams. The culture of higher education is shifting, and the most unsettling change is that many students no longer consider using ChatGPT for homework and tests to be cheating. To them, it feels like a legitimate tool, as ordinary as a calculator or a dictionary. That illusion is dangerous because it erases the line between mastering knowledge and outsourcing it. Students exploit so-called large language models, professors look away, and the result is a crisis that cannot continue.

Higher education’s credibility depends on the public’s belief that a degree represents verified human competence. Higher education’s credibility depends on the public’s belief that a degree represents verified human competence. If that trust erodes, every institution that relies on trained minds, from accounting to medicine to engineering, will feel the consequences. Chatbots are changing the nature of education, and it’s understandable that America’s professors are uneasy. AI can now push and prod each individual student in any subject as effectively as the best professor. This isn’t science fiction; it’s here. There will be time for meetings, committees, and long discussions about how best to augment the professoriate. What cannot wait is action to protect the academic integrity of higher education.

The RSI online-compliance paradigm has failed. That is painfully obvious to both professors and students. The only people who don’t see it are the compliance officers whose jobs depend on the current system. The choice isn’t whether to change; the change is already underway as an AI-augmented educational paradigm emerges. The real question is which direction we will take: requiring authentic human verification through proctored assessment or surrendering verification entirely and admitting that degrees measure time served rather than knowledge earned. Our choice will determine whether degrees remain signals of verified competence or devolve into purchased credentials—and whether institutions built on professional trust survive the transition.

James Andrews is a CPA and professor of business administration at Ohlone College in California, where he writes on higher education, labor markets, and artificial intelligence.