Nuntapuk, Adobe Stock Images

Nuntapuk, Adobe Stock Images Sir Roger Scruton wrote in How to Be a Conservative that “the work of destruction is quick, easy and exhilarating; the work of creation slow, laborious and dull.”

Conservative higher-education reformers would be wise to remember this. While there is much excitement in ripping down ridiculous, wasteful, and harmful bureaucracies in universities, the real work of improving them takes attention to detail, expertise, and care.

The real work of improving universities takes attention to detail, expertise, and care. In the past year, Missouri leaders have attempted to balance the exhilarating with the dull when it comes to reforming the state’s higher-education system. On the exhilarating front, the governor published a splashy executive order eliminating all DEI programs in public institutions. This built on previous work from the legislature that sought to kneecap DEI offices in the state’s universities. But it is the dull work that might actually have a longer tail in reshaping higher education in Missouri. Provisions related to credit transfer and career and technical education might be the key that unlocks important improvements.

It is the dull work that might actually have a longer tail in reshaping higher education in Missouri. Crushing DEI

In February, Governor Mike Kehoe published an executive order “directing all Missouri state agencies to eliminate Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives and ensure compliance with the constitutional principle of equal protection under the law.”

Some may forget that Missouri universities were on the leading edge of racial unrest after the Ferguson riots of 2014. In 2015, the Mizzou football team threatened to boycott its game against BYU unless the president of the university resigned, which he did. Professor Melissa Click made national news calling for “some muscle over here” to try and remove a student journalist from a demonstration. Many of the tactics, rhetorics, and demands that became more widespread in the summer of 2020 were germinating at Missouri universities years before.

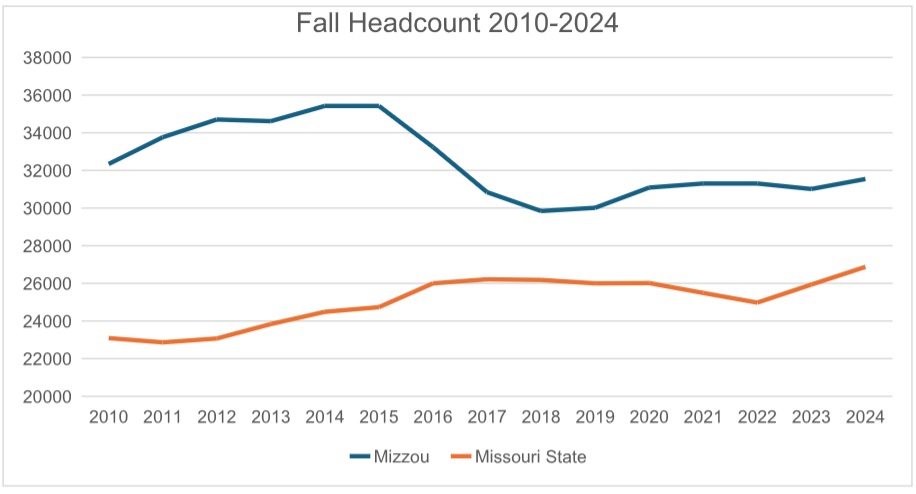

The reputational hit that Mizzou took showed up in enrollment figures. Below is what the university system reported as the total student headcount from before the unrest until today. As a point of comparison, I included Missouri State’s fall headcount for the same period to show that the decline was not a secular trend across the state.

Mizzou is just getting back to 2010 enrollment levels after a huge post-2015 decline.

This is the backdrop against which both the state legislature and the governor decided to rein in DEI practices on campus. Mizzou’s “IDE” office (Inclusion, Diversity, and Equity) was opened in 2015 in response to protests on campus, and similar offices were created at other state universities. The university shut down the IDE office in 2024 both in response to pressure from the state legislature, which advanced but did not pass legislation eliminating DEI programs, and because it seemingly saw the wisdom in some critics’ arguments. As system leader Mun Choi put it, “It’s important that we do not become an institution that excludes in the name of inclusion.”

Missouri’s efforts illustrate the whac-a-mole game that is eliminating DEI in modern universities. At the same time, it’s not clear what the practical effect of such closures has been. In the same story that quoted Choi, the outgoing leader of the IDE office was said to have told staffers, “Every staff member who currently works on inclusive excellence, who works with our faculty and staff, will remain here. Our stakeholders are going to come and see the exact same people who cared for them [before].”

It is challenging for a state legislator or governor to have the kind of granular knowledge to understand what administrators are doing with their time. Missouri’s efforts illustrate the whac-a-mole game that is eliminating DEI in modern universities. It is challenging for a state legislator or governor to have the kind of granular knowledge to understand exactly what administrators are doing with their time. The person who was once a director of a DEI center can move into a role as director of student well-being or some such and keep on doing exactly what she did before.

SB150

If DEI-smashing was exhilarating for Missouri leaders, the passage of an omnibus higher-education bill that took months to make its way through the legislature was slow and laborious.

SB150, the legislation in question, made many changes to higher education in Missouri. (Among them were modifications to the requirements to get licensed as a funeral director and embalmer. I know folks were dying to get that taken care of!)

Two particularly interesting changes showed up in the law. The first was a new requirement to create a 60-hour core curriculum that can easily transfer between community colleges and four-year institutions. This core will serve as a start for five program areas: business, elementary education, general psychology, nursing, and biology. Any institution that offers a degree in these fields will have to accept the core, dramatically easing the transition from a community college to a four-year institution or from one four-year institution to another. This all will need to be in place by the 2028-29 school year.

The second interesting change relates to career and technical education. Currently, the state operates the A+ Program, which provides funds to Missouri students to attend community and technical colleges. Unfortunately, many career-certificate programs were not eligible for A+ Program funding, and some are not eligible for federal Pell Grants either, forcing students to pay for them entirely out of pocket. A new provision in SB150 will qualify more programs, particularly shorter-term certificate programs, for A+ Program-like funding. Eligibility criteria will remain the same.

Both of these measures create more support for students looking to spend less time in traditional educational environments. The community-college core curriculum means that many students might need to spend only two years at a four-year institution. The career-and-technical-education (CTE) support means that some students might not even need to attend a community college to get postsecondary education.

If we’re to project some likely outcomes, the first is cost savings. Educating students at community college is less expensive than doing so at four-year institutions. Credential programs can be less expensive than community colleges. Moving students who would spend time at a four-year institution to a community college, and those who might be at a community college to a certification program, could save both taxpayers and students money.

If we’re to project some likely outcomes, the first is cost savings. The second likely result is a tighter alignment between student needs and the education that they receive. For students who see higher education as a means to an end and have a clear idea of what they want to do, having a streamlined core set of classes that they can take for very low cost close to home can ease the burden of higher education. The same is true for those who have a specific job or skill in mind. They can find a certificate that either teaches the skill or grants them access to that profession. They don’t need to be in community college for two years. Get them the knowledge and the credential, and get them on the job site.

The third likely result, and something interestingly related to the anti-DEI efforts of the legislature and governor, is that the changes to the core curriculum and CTE funding could act as a backdoor way to undermine DEI and other administrative-bloat issues at four-year institutions. It’s generally accepted that DEI issues, campus protests, and the like are far less common on community-college campuses than at four-year institutions. Community colleges do not have the same student-affairs infrastructure in which DEI or DEI-like administrators and programs reside. Having more students spend more time in institutions with streamlined administrations, fewer DEI apparatuses, and a let’s-get-to-work ethos will save students from having to deal with excessive DEI entanglement.

Missouri leaders have put together an interesting combination of splashy cultural initiatives and quiet but thorough reforms to higher education. It will be interesting to see which ones effect the most change in five or 10 years.

Michael Q. McShane is national research director for EdChoice and the coauthor, recently, of Getting Education Right: A Conservative Vision for Improving Early Childhood, K-12, and College.