In the fall of 2020, Cairn University in southeastern Pennsylvania implemented a revised core curriculum that introduced, among other things, a new required course in civics and government. Reactions to this move have varied. Some critics and detractors view any teaching on the American founding or civics as either partisan indoctrination or a form of jingoism. Others appreciate Cairn’s making civics instruction a priority.

There are not nearly enough institutions of higher education that require such a course for all students. Many of those that do are private colleges or universities of a more conservative stripe, culturally and philosophically. Cairn University is such a school, yet it does not possess the characteristics of those institutions that are openly and assertively politicized on either the right or the left. Cairn does not publicly embrace or endorse candidates or elected officials, does not leverage students for political or social activism, and does not publicly criticize or champion today’s partisan political players. This kind of politicization is not the intent of the university and did not drive the creation of a civics requirement (or the content of the course itself). Understanding the actual how, why, and what of Cairn’s move may help readers grasp the value and necessity of such a course in higher education.

In Cairn University’s judgment, civics instruction was both missing and sorely needed. Now in its sixth semester, POL 101 enjoys a favorable reputation among students and has even provided the impetus for the launching of a new politics, philosophy, and history program. The newly required course is quickly becoming a distinctive for Cairn and serves as an example of how smaller and nimbler schools can move quickly to meet student needs.

As I explained in a previous Martin Center article, Cairn possesses an unusual (but highly effective) governance structure. This assured that the inclusion of civics at Cairn was not thwarted by the faculty wrangling that accompanies curricular changes at so many colleges and universities. Of course, some questions arose internally about the need for such a course, the impact of displacing an existing curricular option, and the objectives and content of the new civics class. However, these “process” questions did not deter the university from addressing a need it saw as glaring.

The rationale for the inclusion of the new course in the core curriculum was partly missional. One element of the institution’s vision is to educate students to serve well in society as good citizens and neighbors. Yet the new course was also a response to changing student needs, knowledge, and sensibilities. The university considered the broader social and cultural shifts for which its students must be prepared. In the school’s judgment, civics instruction was both missing and sorely needed.

Declining civic engagement and a corresponding lack of basic civics knowledge is no secret in America. As the Intercollegiate Studies Institute (ISI) reported in 2011, 71 percent of adult survey-takers failed a basic, multiple-choice civics-literacy test. Additionally, fewer than half of surveyed Americans could name the three branches of government, let alone discuss the important construct of the balance of powers, an essential component of a thriving republic.

The same survey showed that the overwhelming majority of Americans (71.6 percent) believe colleges should teach America’s heritage, including her founding documents and the importance of good citizenship. If there is this much consensus around the importance of civics instruction, why are colleges and universities not taking a more active role?

Cairn understood that developing and requiring such a course would run counter to curricular trends in other higher-educational settings. However, the institution determined that its new requirement was a reasonable response to diminishing civic literacy and participation in the broader culture. The POL 101 course at Cairn was born of a genuine concern for society and a commitment to the university’s longstanding mission. Yet it also had to have a simple and coherent design to teach students what the American republic is and how it functions.

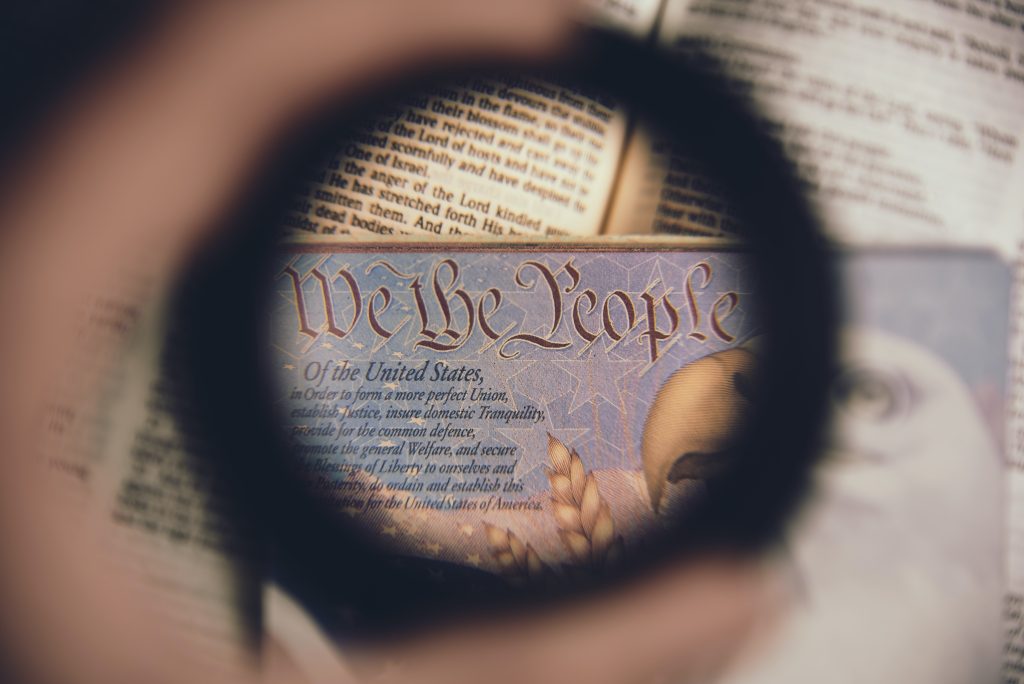

Cairn’s civics course is not designed around political or social agendas, activism, ideologies, or partisanship. As such, the course is not designed around emotional reactions to current events, political or social agendas, activism, ideologies, or partisanship. It does not feed the identity politics of the day or assume the inherent brokenness of the constitutional republic so meticulously framed by America’s founders. Instead, the course leans heavily on the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution and includes readings of original sources, among them the Magna Carta, the Federalist Papers, and several Supreme Court decisions. The course also requires students to satisfactorily answer questions taken from the U.S. Citizenship exam given to immigrants.

Cairn’s POL 101 is divided into units that build upon one another and culminate in a consideration of the responsibilities of an informed citizen. These units provide an examination of philosophical issues ranging from human nature to individualism to constitutionalism, all of which present a context for the American Founding. The course further requires students to work through the articles of the U.S. Constitution that define and limit the government, provide structures and clarify functions, and balance power between the branches. Students examine each branch, how it works, and its relationship to the other branches before examining the Bill of Rights and discussing the amendments. Cairn students are taught what the Constitution says about elections and representation. They are taught why the electoral college was created and how it works, so they can decide for themselves whether its benefits outweigh its liabilities. Finally, students are taught that rights are not given by the government but are to be protected by it—that individual liberties are the truest measure of the equality accorded by the Constitution.

POL 101 is not designed merely to inspire students to “be a voice for change.” Rather, it hopes to teach the concept of self-governance, its fragility, and how its expression and preservation are achieved through voting, as expressed by the Constitution’s framers. These technical aspects of the founding and American civics are essential not only in forming students’ political attitudes but in developing their sense of responsibility as citizens.

America’s fifth president, James Monroe, once wrote that “the question at the end of each educational step is not simply ‘What has the student learned?’ but ‘What has the student become?’” Students becoming informed and responsible citizens is a noble end, and civics instruction at Cairn may prove to be an effective step toward it.

Todd J. Williams is president of Cairn University.