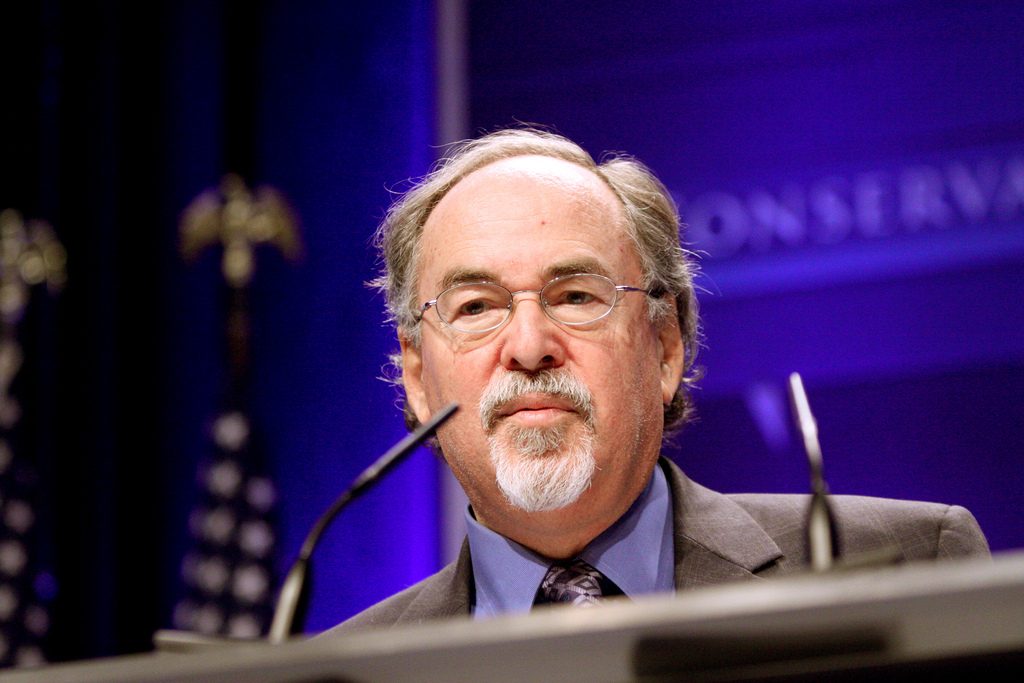

For a few years in the mid-2000s, David Horowitz was one of the most prominent figures on the campus scene. He didn’t have a PhD and he didn’t belong to any discipline or department.

He was, instead, a hard left activist in the 1960s and part of Black Panther leader Huey Newton’s inner circle. Then, after breaking with the Panthers, Horowitz authored his memoir Radical Son, and founded the Center for the Study of Popular Culture (now the Freedom Center).

None of those activities made it onto the radar of academics in the 1990s and just after the turn of the century. Few professors at that time paid much attention to intellectual discourse outside their fields and criticism of the academic enterprise at large. If they came across Horowitz’s name and read that he disliked the shift of the humanities toward political matters or that he was a militant Sixties socialist who’d gone over to the Right in middle age, that was enough for them to ignore him.

For most of his post-left adulthood, Horowitz had aimed his criticisms at radical politics and ideas generally. He knew that the New Left in the Sixties found the campus a congenial place for protest and utopianism, but it didn’t seem to have triumphed there all that much in the following decades. In the 1990s, however, he began focusing more and more on higher education as a particularly vulnerable spot.

By 2005, Horowitz was in the education press all the time and speaking on campuses everywhere. The Left could no longer ignore him.

For my own part, I witnessed identity and sexuality studies burgeon in the humanities in the late-1980s and thought at the time that nobody outside their little coterie would ever pay attention to them. Other conservative critics of academia laughed about how the humanities in the 1980s and 1990s had become the place where failed Marxist visions settled down to die.

David Horowitz thought otherwise.

The leftist notions that had lost out in public life (for example, that socialism would work beautifully if only the right people were in power) retired to the quad where tenured radicals could reiterate them to rising generations who didn’t know of their record of ineffectiveness. There, Horowitz believed, the professors sent half-educated graduates into society who were enthusiastic about progressive reform and identity politics. Certain zones of the campus (especially the humanities and the various “studies” programs) had become indoctrination centers. If they weren’t curbed, the political errors of the past would be repeated in the present.

And so Horowitz started his campaign for the Academic Bill of Rights, which was centered on the fate of students who had resisted this indoctrination and were punished for it. Horowitz started his campaign for the Academic Bill of Rights, which was centered on the fate of students who had resisted this indoctrination and were punished for it.

When I first heard about it, I’d been tracking Horowitz for several years, trying to figure out why the critiques of this rogue intellectual fit my experience of academia, which often left me baffled. I had been accustomed to the college campus as a liberal/left enclave in American life for so long that I couldn’t quite understand how odd that situation is. How could Berkeley, Amherst, Tulane, and Ohio State be zones of progressive change when they aimed to be prestigious, selective, superior institutions?

My colleagues talked all the time, too, about teaching other cultures and traditions, fresh perspectives, and critical thinking. “We must challenge their assumptions, all of them!” was the command. But it took no special insight to see that most of the university doesn’t work this way.

The “challenge conventional ideas” routine was just that, a routine, a conventional anti-conventionalism, a set and stable anti-foundationalism. And how could it not become so after a few years of practice and the novelty wore off?

Horowitz helped me realize that an institution dominated by liberal norms and ideas, but functioning in conservative ways, puts leftist professors in an impossible position. They want a better future—more diversity, fewer bars to personal fulfillment—but they must sustain and repeat an aging past of critical theory while working for a business that, in their own opinion, grows ever more “corporate” and utilitarian.

Nobody wants to give up a tenured post, though. The perks and pay are too nice. So they try to accommodate both obligations—the progressive dreams and professional duties. They instruct the young in old things, yes, but at least they’re iconoclastic and progressive old things. They work in the special zones of exclusive schools, but at least they can turn parts of the acreage into safe spaces and reserves for marginalized identities. They inhabit one of the most hierarchical habitats on earth, but that doesn’t stem the egalitarian, anti-discrimination talk at all.

As a result, you can’t pin them down. One of the great frustrations over the years has been to watch libertarians and conservatives catch them in one inconsistency and contradiction after another—for instance, their steady insistence on diversity at the same time that conservatives have disappeared from their ranks—and believe they have scored serious hits in academic and public debate. But nothing changes. Liberal professors just shrug and go back to work.

This is why the affair of the Academic Bill of Rights is illuminating and deserves to be remembered. Happily for us, Horowitz assembles the story in his just-published volume, The Left in the Universities.

When he crafted the campaign, Horowitz never assumed that strong arguments against leftist praxis would accomplish anything. When a good portion of academic belief follows from postmodern axioms against objectivity and rationality, one can’t expect academics easily to accept evidence that disconfirms their dogmas.

I was once on a national committee setting standards for high school English, and when it came time to draft canons of logic, one member objected, stating that all logical arguments unfold within political contexts. In other words, cogent premises, justified conclusions, and reliable data only go so far. There is always a bigger picture to consider. The consequences of an argument are more important than its validity.

The story Horowitz tells in The Left in the Universities is a case study in this “situational” way of thinking and acting. In response to reports of liberal professors bullying conservative and libertarian students, Horowitz had drafted the Bill and set about pressing states and institutions across the country to adopt it. The remarkable element in the narrative is not the document itself, which Horowitz modeled on AAUP principles, nor was it his campaign tactics, which resembled dozens of other left and right advocacy projects.

Instead, as he recounts again and again, it was the underhanded, smearing way in which the faculty and administrators went on the counterattack.

One episode is exemplary. When Horowitz sent a draft of the Bill to the AAUP for comment and revision, his contacts there ignored him and stonewalled before finally issuing a statement on their website, not to Horowitz himself. They called it “a grave threat to fundamental principles of academic freedom.” The AAUP especially objected to the demand that schools “maintain political pluralism.”

But, Horowitz countered in his reply, “The Academic Bill of Rights calls for no such requirement and does not employ the term ‘political pluralism.’” The AAUP also accused the Bill of allowing or, rather, asking for the representation of despicable opinions in classrooms. The actual text of the Bill, however, only requires that schools “foster a plurality of methodologies and perspectives.”

It is clear from the document that the methodologies and perspectives must meet academic standards; for instance, teaching economics not just from a Marxist perspective but including libertarian and other common, respectable positions as well.

But the AAUP distorted this academic plurality into an immoral free-for-all:

No department of political theory ought to be obligated to establish “a plurality of methodologies and perspectives” by appointing a professor of Nazi political philosophy, if that philosophy is not deemed a reasonable scholarly option within the discipline of political theory.

As Horowitz notes, this was not a misunderstanding. It was an Orwellian accusation. It raises a fantastical prospect (“we must hire a Nazi”) in order to sweep the Bill of Rights off the table.

The AAUP had no interest in engaging Horowitz. It only aimed to discredit him, and if that meant distorting the plain sense of the document, so be it.

There are many more instances of anti-intellectual, anti-academic behavior in The Left in the Universities. Every academic who engages with administrators and colleagues on matters of curriculum and funding and campus events should read it. The essays contained in it date from a decade and more ago, but they display the particular talent Horowitz brought to academic politics in those early years of the century.

He identified the issues that caught the faculty in the acute contradictions outlined above, and he devised reforms that led them to expose their double-dealing professional lives so absurdly that one couldn’t regard them as responsible, thoughtful people anymore.

Horowitz quotes a letter from a Smith College professor who scoffed at his insistence that the classroom not become a site of indoctrination. “As for admitting that I ‘indoctrinate’ my students instead of teaching them, tell me my friend, when has there ever been a difference?”

When Horowitz sits in on a general political science course on industrial societies at Bates College and asks the teacher why she has only one assigned text, an anthology of cultural Marxism, the teacher replies, “Well, they get the other side from the newspapers.”

No allegation of leftist tyranny in the classroom by a conservative or classical liberal is as damning as the words of the professors themselves that Horowitz provoked.