The fact that conservatives are outnumbered on college campuses isn’t groundbreaking news. The amount of ink that’s been spilled recounting the left’s stronghold on the academy and the threats that such ideological imbalance poses to rigorous academic inquiry—not to mention the perverse effects it wields on the culture—has been enough to fill volumes of journals, articles, and books.

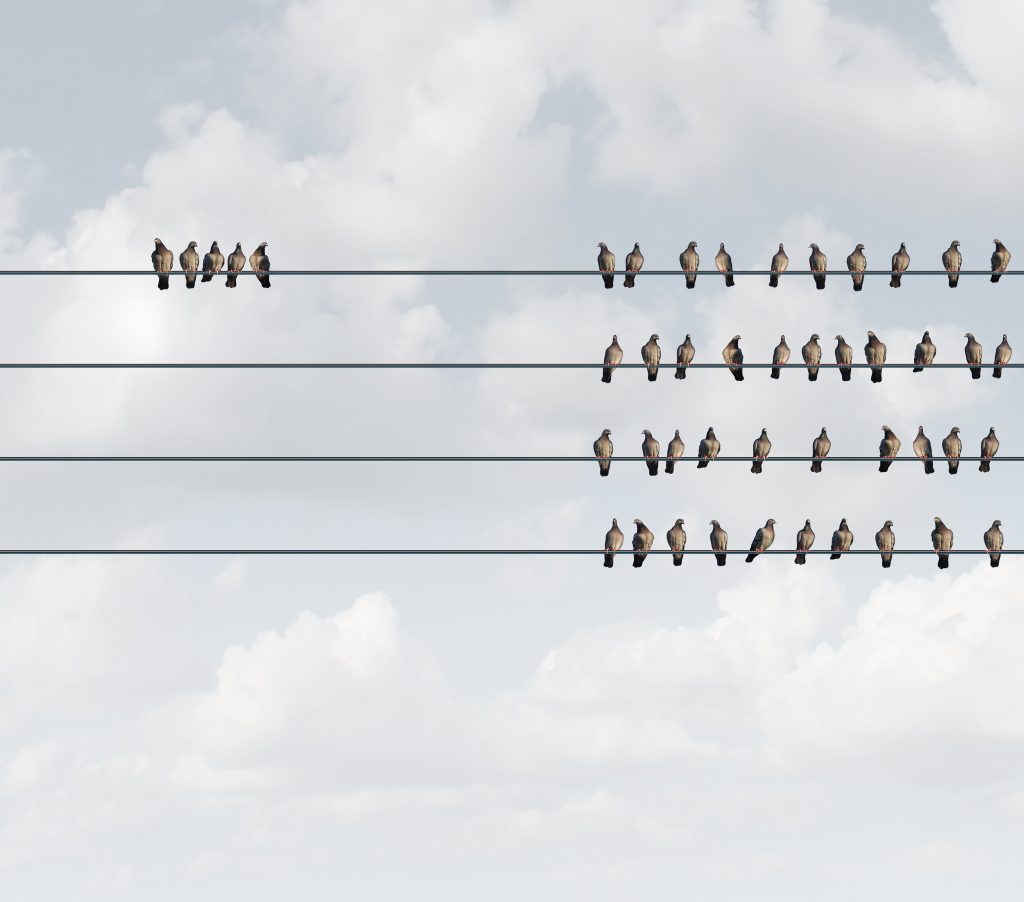

But, given that robust dialogue and competing ideas are crucial for the pursuit of truth, the need to shine a light on higher education’s ideological homogeneity is crucial until a healthier balance is established. A recent talk by North Carolina State University political science professor Andrew Taylor did just that.

On October 22, Taylor gave his remarks at an event hosted by the ICON (Issues Confronting Our Nation) lectures series. ICON is a non-profit organization based in Durham and Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Taylor’s talk was entitled “Minority Report: The Status of Conservatives on the 21st Century College Campus.” Taylor likened his talk to a “state of the union” address regarding the dearth of conservatives in academia.

Taylor started his talk by describing the climate on college campuses and provided a wealth of data to illustrate the academy’s ideological imbalance. He first focused on the deficit of conservative faculty members in many departments.

The ratio of liberal to conservative political science faculty, for example, is startling— something that Taylor discovered in a study he conducted with Lonna Atkeson, a political science professor at the University of New Mexico. The study, “Partisan Affiliation in Political Science: Insights from Florida and North Carolina,” was recently published by the American Political Science Association.

For their research, Atkeson and Taylor collected hard data of the political affiliations of political science faculty at public institutions in North Carolina and Florida. Among political science faculty, they found that Democrats outnumbered Republicans 6.8 to one. He noted that that ratio is mostly the same in both states. Those ratios were particularly high among female faculty and, interestingly, among senior faculty. It appears that the more senior faculty members are, the more likely they are to be Democratic.

Taylor then pointed to research from economist Mitchell Langbert. Langbert conducted a survey of professors from elite liberal arts universities and used their party registration to determine their political leanings. He found that Democrats outnumbered Republicans 5.5 to one in economics, 17.5 to one in philosophy, 44 to one in English, and 48 to one in sociology.

In terms of students, Taylor noted that student bodies are moving to the left—though not dramatically. A recent survey found that about 50 percent of millennials and generation Zers would prefer to live in a socialist country. Nevertheless, the results of a survey Taylor conducted in 2017 indicate that some students still consider themselves to be more conservative than their professors. The survey was sent to 200 NC State University students who were taking an introduction to American government class.

Of the students who responded to the survey, 52 percent said they were liberal, 28 percent said they were conservative, 39 percent said they were Democrats, and 29 percent said they were Republicans. Even though NC State’s student body clearly leans left, 49 percent believe that the faculty were to the left of them politically. Taylor emphasized that this is a significant portion of self-identified liberal students who thought themselves to be less liberal than their professors.

Taylor then turned his attention to university administrators—who might be the biggest threat to conservatives on college campuses. At NC State, the budget for administrators has steadily increased, sometimes at a greater rate than the budget for instruction, Taylor reported. He also pointed to the results of a national survey conducted by Samuel Abrams of Sarah Lawrence College. In his survey, Abrams found that in the social sciences, liberal administrators outnumbered conservatives by about 6 to one. In New England, that ratio was 28 to one.

The clear ideological imbalance of college campuses is concerning for several reasons.

First, students might unthinkingly accept left-leaning world views offered by their professors, which in turn could inform their behavior. While it is true that empirical studies, particularly in political science, show that the ideological leanings of professors do not have drastic effects on students’ fundamental political beliefs, that doesn’t mean professors don’t have any influence over their students.

Indeed, Taylor said that social science research suggests that “even small effects can have a profound impact on certain other kinds of behavior.” As an example, Taylor pointed to how campaign advertisements have been shown to have large effects on how people decide to vote. He continued:

If social science has shown these kinds of influences, a semester—15 weeks, three hours a week—talking about political, social, economic issues, with someone in a position of authority has got to have some kind of influence on students. The effect might not make them turn into a lifelong liberal, but it could have profound effects at that particular time, or how they vote in elections. At least for a small period of time.

A second concern with the lopsided faculty composition is that professors, like everyone else, are susceptible to innate bias—which in turn could affect how they grade their conservative students. “When we’re doing our grading, are we going to be biased? The social science research suggests: yes we are,” Taylor said.

Another worry is that a lack of ideological diversity hampers students’ intellectual development—especially that of liberal students. That’s because, in a climate heavily dominated by progressive ideas, liberal students have less exposure to alternative viewpoints that challenge their beliefs. Taylor referenced a 2014 article written by Duke University political science professor Michael Munger that argued conservative students have a special advantage because they are exposed to varying points of view.

In his article, Munger cited John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty where Mill argues for the need to hear all sides of an argument:

He who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that. His reasons may be good, and no one may have been able to refute them. But if he is equally unable to refute the reasons on the opposite side, if he does not so much as know what they are, he has no ground for preferring either opinion.

Curricula have also suffered from the left’s dominance of the academy. Courses on important topics such as diplomatic history, war history, and influential Western philosophers aren’t required on many college campuses anymore. And the curriculum is filled with what Taylor called “vanity courses:” Courses that are “reflections of [professors’] own research interests, or, increasingly, their own political interests.” Taylor said that these kinds of curricula are typically found under “new fields of inquiry” such as cultural studies, gender studies, and racial studies.

The problem goes beyond the classroom and infects research and scholarship as well. For those pursuing a career in academia, it’s common to hear the phrase “publish or perish.” It is crucial for an aspiring academic to have his or her research published in a scholarly journal. Those who decide what does—and does not—get published have a great deal of power over faculty hires. That’s why Taylor referred to staffers of academic journals as “the gatekeepers.” “If they don’t like what you’ve written, you don’t get published,” he said.

And there is reason to believe that some academic journals prioritize the promotion of “social justice” ideology at the expense of academic rigor. Taylor pointed to the fake articles submitted by James Lindsay, Helen Pluckrose, and Peter Boghossian that were successfully published in academic journals. The authors employed popular social justice jargon to argue for absurd conclusions such as fat bodybuilding should be a sport or white male college students shouldn’t be permitted to speak in class and should be forced to sit on the floor in chains.

Taylor also spoke about the possible indirect effects of the ideological imbalance on college campuses. For one, it could discourage young people from pursuing careers in academia. Since training for a career in academia already involves a number of opportunity costs, the prospect of being persecuted for one’s conservative beliefs—and perhaps not being able to get a job—might dissuade aspiring conservative academics.

To conclude his talk, Taylor reviewed some solutions that might help restore intellectual diversity on campuses. First, academics, students, parents, and taxpayers should demand that colleges and universities be transparent about the subject matter that is taught. One way to do this, particularly at public institutions, is to make course syllabi publicly available.

Secondly, alumni should keep their alma maters accountable. An effective way to enforce accountability is by withholding donations from institutions that fail to uphold intellectual diversity. Donors can also direct how their funds are used, instead of writing a blank check to a university.

A final possibility is to create separate conservative institutions, centers, or departments. Taylor referenced a recent National Affairs article by Fredrick Hess and Brenden Bell entitled An Ivory Tower of Our Own which makes the case for the creation of an alternative research university that can serve as an “incubator” of conservative ideas.

In the end, Taylor’s account of the status of campus conservatives, although sobering, serves a much-needed purpose: it shines a light on academia’s entrenched bias. Unless that bias is remedied with a healthy competition of viewpoints, colleges and universities will continue to stray from their central mission of truth-seeking.

Shannon Watkins is senior writer at the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal.