In an earlier millennium, yours truly undertook graduate studies in history and persisted a couple of years before getting cold feet. Some new PhDs could not find academic positions; some transferred into the university’s MBA program. I retooled in statistics and computer programming.

Grad students in English faced similar choices, with two differences. First, it was easier to drag out a wretched graduate-student existence in English because grad students were needed to teach required freshman-composition courses. Second, a good job market existed for teachers of writing, as opposed to literature.

Some I knew refused to consider the latter option. The nature of the work certainly differed. Lucky literature teachers passed their days discussing their own favorite books with interested or captive students. Writing teachers, by contrast, could not avoid the toil of many hours focused on details—reading and editing teenagers’ often execrable scribblings. More work, less fun.

English departments must now compete with college majors that either did not exist or barely existed decades ago. That was over 40 years ago. Though universities’ required freshman courses back then were titled English Composition, often they were literature courses in disguise. Peruse university undergraduate requirements on the web today, and one can see that many universities have switched to a focus on practical writing skills over the years.

Undergraduate requirements are now frequently labeled and described more explicitly as courses in writing. Today, many freshman writing instructors wishing to indoctrinate their students in a favorite ideology du jour must nevertheless demonstrably improve their students’ composition skills, especially where there is an externally administered writing test at the end of the term.

Despite such adaptations from many English departments, one now reads in The New Yorker that English department enrollments are “in free fall.” For empirical support, The New Yorker’s essay (and other recent articles) refer to data, and interview data managers, from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences’ Humanities Indicators program. Yet collecting complete and reliable college major and degree-completion data from all U.S. postsecondary institutions across the years requires an enormous amount of work, as well as some power to coerce compliance that is unlikely to exist with a voluntary private association such as the AAAS.

In this case, the data source behind the data source happens to be the U.S. Education Department’s National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). Its Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) has collected these types of data for more than half a century.

Peruse their table entitled “Bachelor’s degrees conferred by postsecondary institutions, by field of study: Selected academic years, 1970-71 through 2020-21.” One can see that the number of English degrees has declined over the years, even as the total number of bachelor’s degrees has more than doubled.

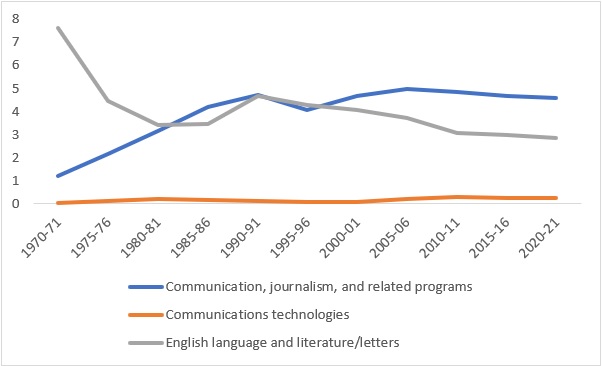

Widen the focus to examine the entire table and read the footnotes, however, and one may notice that English departments must now compete with some college majors that either did not exist or barely existed decades ago. Moreover, some of these other majors happen to be closely related to the English major, though offering more applied, practical studies. The following chart compares the trends in college degree completion between the early 1970s and 2021 in three IPEDS fields: “English language and literature/letters”; “Communication, journalism, and related programs”; and “Communications technologies.”

English bachelor’s degree completion declined from about 7.6 percent of all degrees in 1971 to about 2.8 percent in 2021. The New Yorker’s “free fall” focused on the trend from 2012 on, when English bachelor’s degree completion fell another 0.22 percent after 15 years of steady decline.

If one combines English with the various communications majors, however, enrollments have increased slightly over the years, from 7.6 to 7.7 percent. Thus, while interest in majoring in “literature and letters” may have declined, interest in the craft of writing or speaking in various forms has increased. Some English professors over the years may have jumped over to communications or journalism departments to enhance their job security.

A college student interested in screenwriting would have majored in English a half-century ago. These days? Probably not. A college student interested in, say, screenwriting would have majored in English a half-century ago. These days? Probably not. There exist other programs more tightly aligned to that interest.

Like the English major in particular, the humanities in general are often said to be in decline. How reliable is that story? This next chart compares the trends in college degree completion between the early 1970s and 2021 in “English language and literature/letters” and two other IPEDS fields: “Area ethnic, cultural, gender, and group studies” and “Liberal arts and sciences, general studies, and humanities.”

Compared to the 7.6 to 2.8 percent decline in English majors as a percentage of the whole, the proportion of students majoring in “area” studies or non-English-major liberal arts and humanities increased, from 1.2 percent to 3.0 percent.

What about the “Visual and Performing Arts,” another impractical area of study thought to be in decline? Its proportion of all degrees increased from 3.6 percent in 1971 to 4.4 percent in 2021.

Granted, considerable detail is lost in IPEDS’ classification scheme. Nonetheless, a story of inexorable, unidimensional decline in English and the humanities seems too narrow. A more nuanced story of academic trends should at least include the following themes:

- A general trend away from traditional, “pure” programs of study to more applied, vocational, and skill-based programs;

- A proliferation of college majors in general, including more design-your-own majors;

- The continuing, even increasing, popularity of some of the content and skills that English departments used to claim as their own, back when they were the only place on many campuses where one could find them.

Like other recent writers on the topic, Adam Ellwanger (writing last month in Quillette) accepts that English Departments are dying. In Ellwanger’s opinion, this is because “professors would rather watch it die than reform.” But he also takes a longer view, writing that “there was never a period [in the past 25 years] when the English major wasn’t in decline.”

One might argue, instead, that at least some of what used to be found in the English department has moved elsewhere on campus and remains very much alive. And perhaps that leaves behind a rump department that can appear hidebound and reluctant to change.

[Editor’s note: This piece has been updated to correct minor data errors.]

Richard Phelps is founder of the Nonpartisan Education Group, editor of the Nonpartisan Education Review, a Fulbright Scholar, and a fellow of the Psychophysics Laboratory. He has authored, edited, and co-authored books on standardized testing, learning, and psychology. His newest book is The Malfunction of US Education Policy: Elite Misinformation, Disinformation, and Selfishness (2023).