Peter Hansen, Wikimedia Commons

Peter Hansen, Wikimedia Commons In Texas, we take pride in doing everything BIG. That seems to apply to our university systems, as well. While other states have one or two public university systems, we have six! “Why?” a colleague recently asked. “Wouldn’t Texas be better off merging some of its systems and saving on administrative costs?”

My inner economist immediately balked at this idea. More is generally better, correct? A number of past Nobel laureates came to mind. Certainly F. A. Hayek would agree that multiple systems foster innovation, as each strives to move ahead in the discovery process, experimenting with new models in a dynamic educational landscape. George Akerlof might argue that each system and its individual institutions build a distinct brand and reputation over time, which serves as a crucial signal of quality to students and employers. Elinor Ostrom could highlight the benefits of polycentric governance, which allows individual systems to tailor their programs and rules to the specific, unique needs and circumstances of their local area.

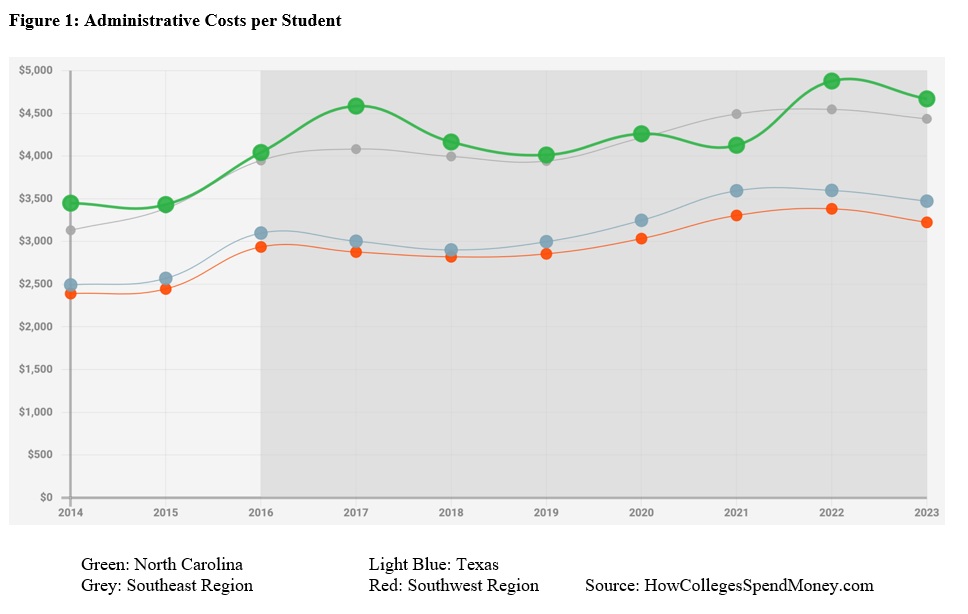

The question piqued my curiosity, so I did a little digging to see how administrative costs in Texas compare to those of North Carolina, where my colleague calls home. The American Council of Trustees and Alumni has built a wonderful tool to compare university administrative costs across the United States. Take a look at the chart below comparing Texas, North Carolina, and their respective regions.

In the past decade, North Carolina’s per-student administrative costs at public universities (green line) have been between $500 and $1,500 more than Texas’s (light blue line), despite the Tar Heel State’s having only one public university system. In the most recent year for which data are available, the difference was about $1,200.

Hayek would agree that multiple systems foster innovation, as each strives to move ahead in the discovery process. I then compared the states’ respective regions to see how they measured up. North Carolina spent more than the average regional cost (grey line) in all but one year. Texas moved closely with its region’s cost (red) for all years, due in part to the fact that it accounts for over half of its region’s public universities. The picture above indicates that the difference in administrative costs between the two state’s systems are likely due to regional differences.

North Carolina’s instructional cost per student is higher than Texas’s, and its administrative costs are higher still. Given that the cost of living is similar in the two regions, we should look for another reason for the discrepancy. One reason could simply be a cultural preference for administration playing a role. Perhaps regional regulation, compliance, and reporting structures require more administration, or perhaps the universities in the eastern U.S. are older, and administrative roles have grown over time. (UNC-Chapel Hill was founded nearly 100 years before UT Austin.) My money would be on the latter, as more time provides more opportunity for administrative bloat.

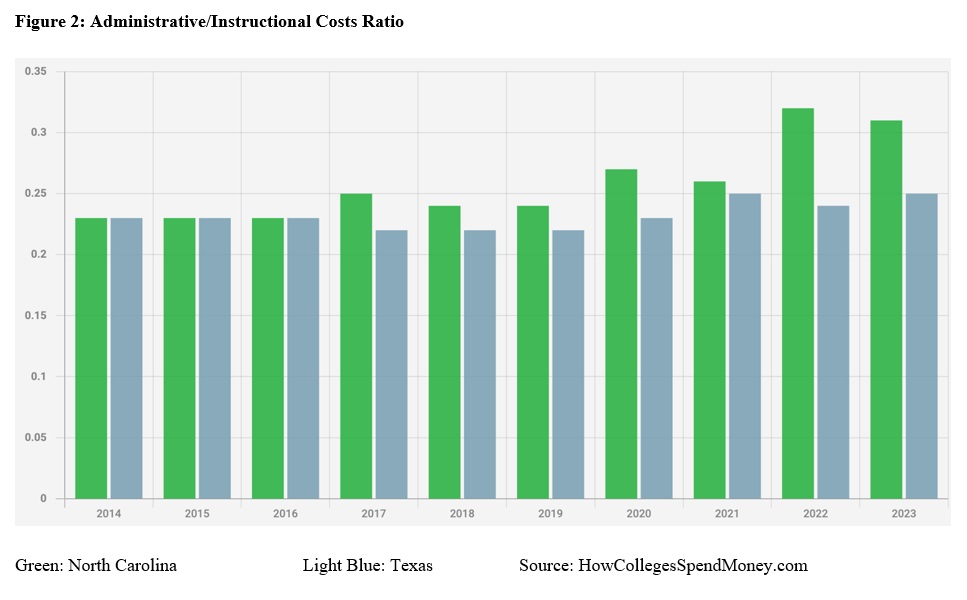

North Carolina’s instructional cost per student is higher than Texas’s, and its administrative costs are higher still, meaning the ratio of administrative to instructional costs is higher in North Carolina.

What’s going on here? The original question was whether Texas could cut administrative costs by merging its six systems into one, matching North Carolina. The numbers above seem to indicate that Texas is already outperforming North Carolina in this metric (although I must admit that I’ve heard many complaints about cutting through “orange tape” during my time at UT; neither state is an exemplar of administrative efficiency). To my colleague, this is counterintuitive, because redundancy of administrative efforts should be reduced by mergers, thereby lowering costs.

Economics 101 would suggest that this is an issue of economies of scale. The firms in some industries can minimize per-unit costs by growing larger. Textbook publishers are a good example. The upfront costs to produce a textbook are large, so a large run will result in a lower per-unit cost. Niche books with small markets tend to cost more. Yet there is also a point at which the firms in some industries can grow too large. This is known as diseconomies of scale. Hospitals are the textbook example. Perhaps you’ve noticed that, with perhaps the exception of very rural areas, hospitals tend to be around the same size. They’re usually as large as a Walmart and smaller than a shopping mall. As a hospital grows beyond the usual size, its administrative costs grow at an increasing rate, contributing to greater average costs of production.

After some point, additional expansion results in higher administrative costs to manage the larger enterprise. Do public universities also face diseconomies of scale? A certain size may need to be achieved to reach the more affordable tuition aims of public higher education, but, after some point, cost savings from expanding operations are reached and additional expansion results in higher administrative costs to manage the larger enterprise.

Enrollment in the University of North Carolina System was over 256,000 this fall, a number very similar to that of the University of Texas, the Lone Star State’s largest university system. If the diseconomies-of-scale argument is true, additional university systems rather than one larger system would be warranted to service additional enrollment in Texas.

If the diseconomies-of-scale argument is true, additional university systems would be warranted to service additional enrollment. Does this mean that states such as Texas and North Carolina have come reasonably close to minimizing their administrative costs and that there is little to no room to reduce them? My economist self certainly hopes not! The work of economics’ most recent Nobel laureates suggests there is yet hope.

In the 1940s, Joseph Schumpeter wrote about a process he called creative destruction. Innovation leads to more efficient means of production and, subsequently, to economic growth. In this process, older methods become outdated, “destroying” obsolete technologies, job skills, and more.

This year, Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt won the Nobel for “having explained innovation-driven economic growth.” Their work points to the importance of a competitive environment to foster innovation, bolster economic growth, and avoid stagnation. They might even view Texas’s multiple systems as a competition that provides an incentive for each system to invest in new research, develop better programs, and create cutting-edge technologies.

In the context of administrative costs, advances in artificial intelligence could provide an avenue to streamline some tasks. Communication, forecasting, course scheduling, financial-aid management, compliance, and reporting are just a few of the areas where AI excels. However, I foresee a few hurdles before cost-saving measures such as these are fully implemented. While creative destruction is hailed as a necessary driver of sustained economic growth, as its name suggests it leaves a wake of destruction in its path. Older technologies become obsolete, those working in dying sectors must be retrained in different ones, and new technologies must be adopted and learned.

In the 19th century, Luddites destroyed spinning machines because those tools could do their work in a fraction of the time with fewer workers. Later, local butchers joined ranks to halt the growth of large meatpacking plants that emerged with the invention of the refrigerated rail car. More recently, a group of people disabled the sensors of self-driving cars to prevent them from operating.

Replacing administrative positions with AI will face resistance in similar ways. Those being replaced will protest, of course. Many have built their careers in the university system, and transitioning to something new is not a simple matter. Likewise, adapting to interfacing with an AI bot rather than a human is awkward for many customers at this point in time, and most of us have an inherent suspicion of experiences that are unfamiliar to us.

While an AI program does not demand a salary, benefits, or sick leave, it lacks the valuable component of human interaction. A student recently confided to me that she prefers Waymo, the driverless ride service available in Austin, because she doesn’t have to talk to an Uber driver when she uses the former. I’ve always been an early adopter of new technologies, but perhaps my older self is starting to exhibit some neo-Luddite sentiments; I was concerned for what attitudes like this may mean for humankind’s future interpersonal skills.

When state and federal budgets support administrative costs at their current levels, I don’t see a strong incentive for university systems to implement cost-saving measures through artificial intelligence or otherwise. Some have forecasted that university enrollments will drop substantially in the coming years. This may provide the catalyst needed to reevaluate how resources are allocated if public spending does not increase to cover the tuition deficit. Until that time, I predict it will be business as usual for as long as state-allocated budgets allow.

Charity-Joy Acchiardo is a senior fellow at the Civitas Institute and an associate professor of instruction in the Department of Economics at the University of Texas at Austin.