TensorSpark, Adobe Stock Images

TensorSpark, Adobe Stock Images The U.S. Department of Education recently announced a reorganization of its Federal Student Aid (FSA) ombudsman’s office into a broader “Office of Consumer Education and Ombudsman.” The aim is twofold: to provide clearer, more proactive information to prospective borrowers and their families before they sign promissory notes and to issue a new “common manual” for loan servicing and collections that standardizes practices across vendors.

At first glance, the reform seems sensible. After all, with federal student-loan debt at $1.8 trillion and millions of borrowers delinquent or in default, something must change. Yet a closer look reveals that, while better information may help at the margins, it does not resolve the underlying problem: The federal loan system itself creates incentives for overborrowing, tuition inflation, and labor-market mismatches. Without deeper structural reforms, even the best consumer-education program will fall short.

The federal loan system itself creates incentives for overborrowing, tuition inflation, and labor-market mismatches. The Appeal of Proactive Guidance

There is no doubt that America’s federal student-loan system is complex, confusing, and inconsistent. As the Department’s own Federal Register notice acknowledges, borrowers often receive conflicting information depending on which servicer manages their account, whether their loan has been transferred, or how a particular vendor interprets high-level guidance from FSA. It is not uncommon for one borrower to be steered toward forbearance while another with the same profile is nudged into income-driven repayment. Transfers between servicers can disrupt auto-debit arrangements, misplace records, and sow distrust. Complaints to the ombudsman’s office consistently reveal frustration with poor communication, unhelpful repayment support, and the inconsistent handling of errors.

Without deeper structural reforms, even the best consumer-education program will fall short. Against this backdrop, the department’s decision to shift the ombudsman from a reactive complaints desk into a proactive educator has intuitive appeal. The office would provide clear, accessible information about the risks and responsibilities of borrowing. It would analyze complaint data to anticipate sources of confusion, produce tools to help families navigate the aid process, and publish a centralized set of servicing and collections standards to bring uniformity across vendors. Students and parents, in theory, would have a better grasp of their commitments before they borrow and more consistent experiences afterward. For a system plagued by opacity and inconsistency, these reforms promise transparency and order.

The Limits of Financial Literacy

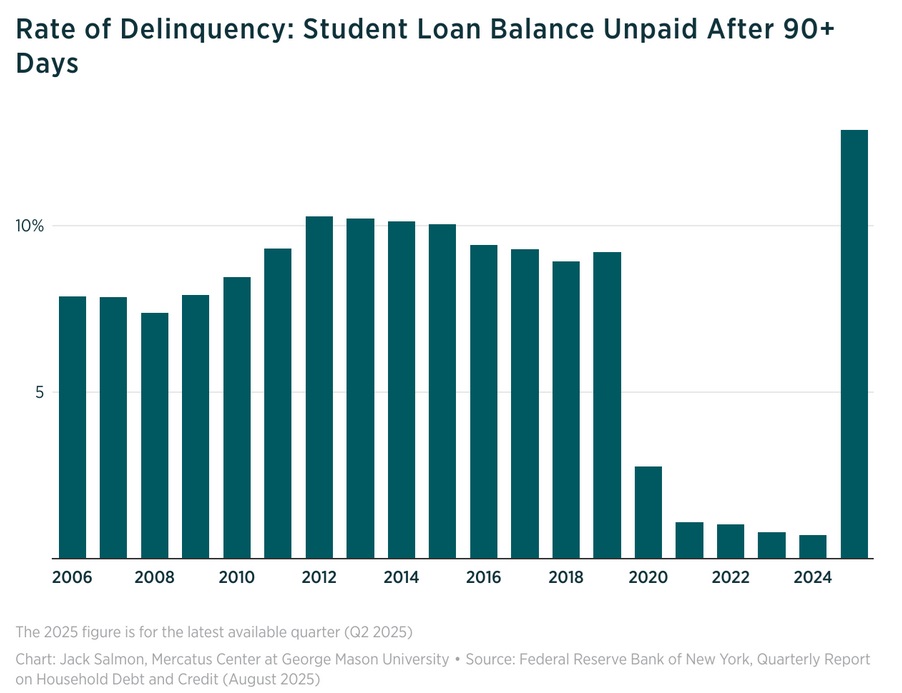

But will better consumer education materially reduce the $1.8-trillion debt burden or the 13-percent delinquency rate? Decades of research suggest the answer is no. Information campaigns can change knowledge but rarely behavior. Financial-literacy courses in high school, for example, have at best modest and short-lived effects on subsequent borrowing, saving, or repayment choices. Students often face cognitive overload when presented with dozens of repayment plans, loan types, and conditional benefits. Even when they understand the basics, the decision to borrow is influenced more by social pressures, cultural expectations, and institutional practices than by neutral information.

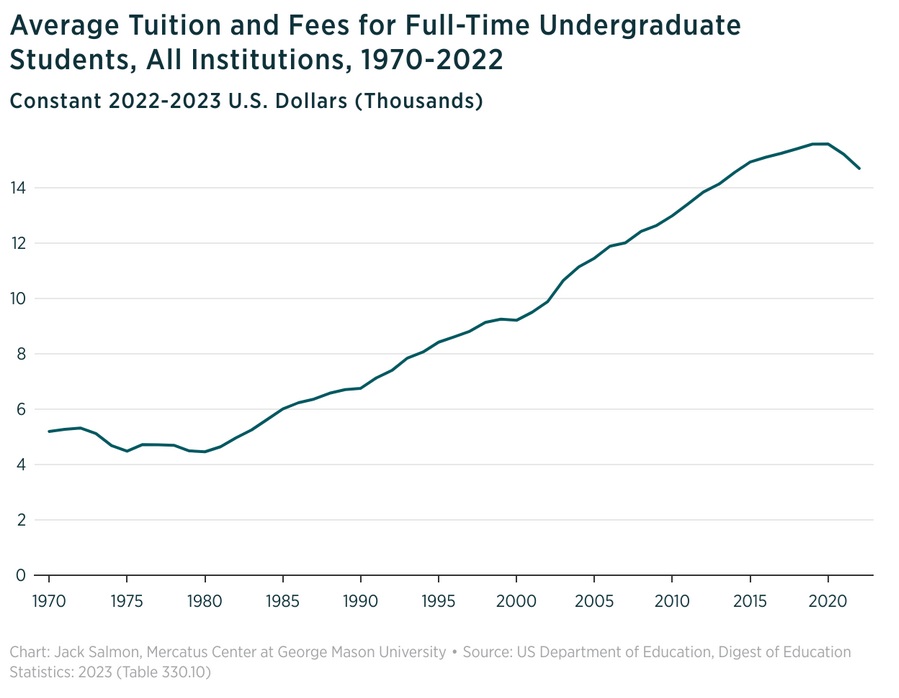

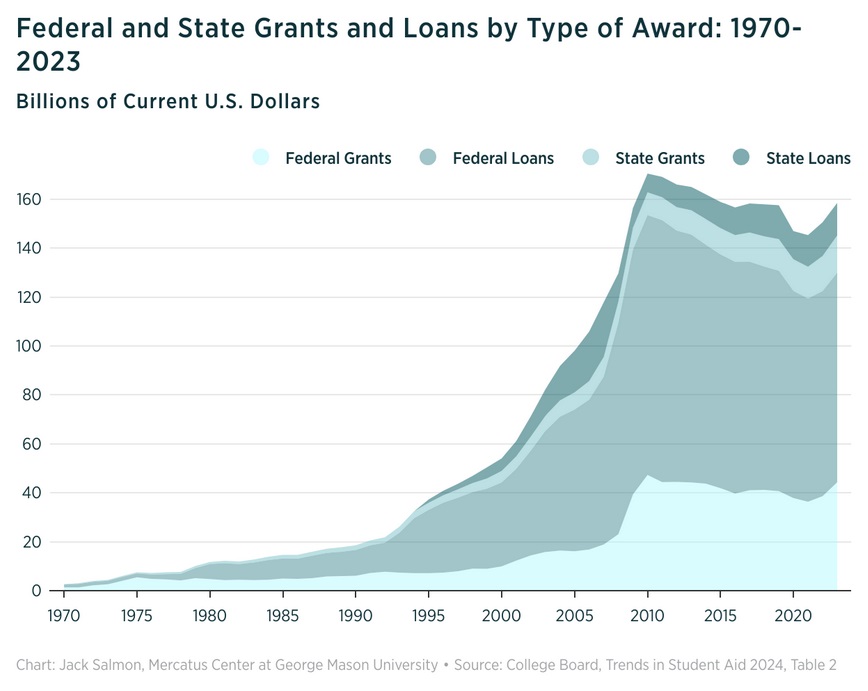

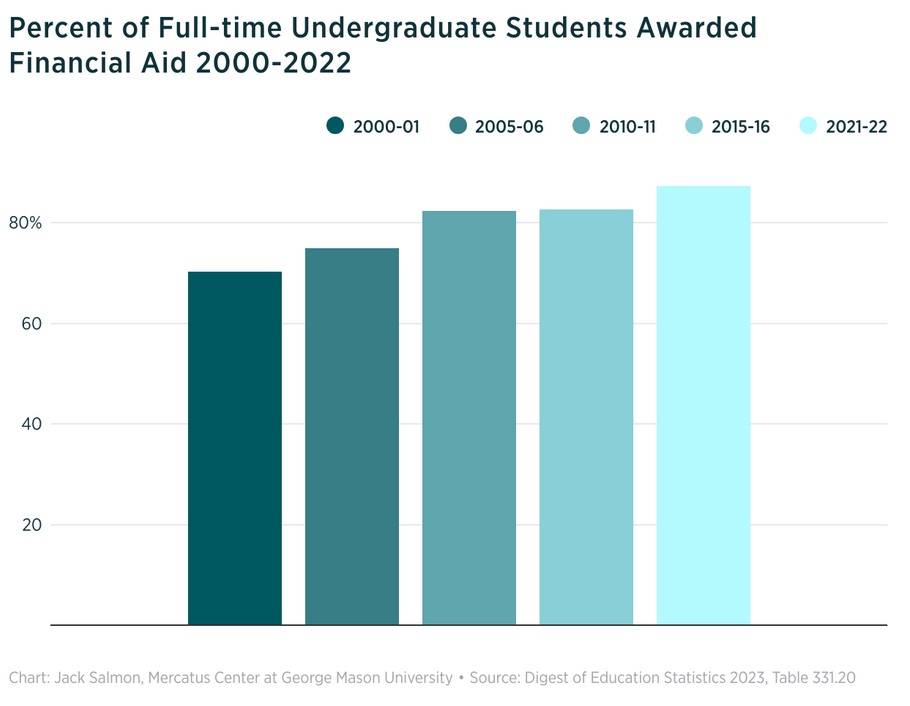

Moreover, the federal loan program itself distorts incentives in ways that consumer education cannot undo. Colleges face little pressure to constrain tuition when they know federal loans will meet virtually any price. Students, meanwhile, are encouraged to borrow more than they otherwise would, reassured by subsidized interest rates, generous forbearance options, and the prospect of eventual forgiveness. These structural forces swamp the marginal effect of improved counseling. The Bennett Hypothesis, that federal aid simply enables institutions to raise tuition, remains the more powerful explanation of rising costs and mounting debt. A pamphlet from the ombudsman, no matter how clear, cannot alter those dynamics.

Servicing Standards vs. Systemic Reform

The second pillar of the department’s plan, the common manual for loan servicing and collections, raises similar questions. To be sure, inconsistent servicing has harmed borrowers. The patchwork of directives and vendor discretion leads to inequitable treatment and needless frustration. A centralized, publicly available manual could bring clarity, standardization, and accountability. Borrowers would know what to expect, and FSA would have a yardstick against which to measure vendor compliance.

Yet the promise of a new common manual risks obscuring a deeper truth: Federal student-loan servicing is inherently political. The department must balance conflicting objectives—maximizing repayment rates, protecting borrowers from undue hardship, and responding to shifting political demands for forgiveness or relief. No manual can eliminate the fact that servicing rules will change whenever administrations shift priorities. The Trump administration’s move to strengthen repayment and transparency follows directly on the Biden administration’s aggressive use of executive authority to forgive billions in loans. Future administrations may swing back toward generosity or crackdowns. Servicers, caught in the middle, will always struggle to provide consistent service when the rules themselves are unstable.

No manual can eliminate the fact that servicing rules will change whenever administrations shift priorities. Lessons from Past Reforms

History offers cautionary lessons. In the 1990s, the Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) program used a common manual to standardize guidance across private lenders and guaranty agencies. While the manual reduced some inconsistencies, it did not prevent escalating defaults in the late 1980s and early 1990s, nor did it stem tuition growth. Eventually Congress abandoned FFEL in favor of the Direct Loan Program, not because information was lacking but because the structure of the program itself was flawed. Similarly, the Obama administration’s expansion of income-driven repayment was heralded as a way to align repayment with borrowers’ ability to pay. Yet it created new complexity, encouraged moral hazard, and shifted costs to taxpayers without addressing the underlying drivers of debt.

A new common manual will not change the reality that tens of millions of Americans have borrowed more than their degrees are worth. The department’s new common manual may help borrowers avoid confusion when loans are transferred or when servicers interpret guidance differently. But it will not change the reality that tens of millions of Americans have borrowed more than their degrees are worth in the labor market. Nor will it address the credential inflation that pushes young people into ever-higher rungs of schooling for jobs that once required only a high-school diploma.

A Better Path Forward

If policymakers are serious about reducing defaults, improving repayment, and protecting taxpayers, they must look beyond consumer education and servicing guidelines. The problem lies not in how loans are communicated or serviced but in how they are structured and disbursed. Three possible reforms stand out.

First, Congress should further lower the cap on federal Parent PLUS loans, which allow parents to borrow excessively high sums for their children’s education. These loans are disproportionately responsible for overborrowing and high default risk. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) will impose a cap of $20,000 per year / $65,000 per lifetime, per student, starting July 1, 2026. Congress should go further by reducing that cap or lowering lifetime limits, to better guard against excessive parental debt burdens. Second, policymakers should expand alternatives to debt financing, such as income share agreements, which tie repayment to actual earnings and align the interests of students, institutions, and investors. Third, and most importantly, the federal government should reconsider its expansive role in financing higher education altogether. By offering near-universal access to subsidized loans, Washington has fueled tuition inflation, encouraged over-enrollment in low-value programs, and shifted risk away from colleges and onto students and taxpayers.

In my own research, I have documented the diminishing college wage premium and the growing mismatch between what universities teach and what the labor market demands. Students often take on tens of thousands in debt for degrees that confer little advantage over alternatives such as vocational training, apprenticeships, or direct entry into the workforce. The tragedy of the student-debt crisis is not simply that borrowers are confused by servicer communications but that they were encouraged to borrow in the first place for degrees that never paid off.

Washington remains deeply enmeshed in a system that is failing students and taxpayers alike. The Political Economy of Student Loans

There is also a political dimension worth acknowledging. The Trump administration’s proposal positions itself as the responsible alternative to Biden-era forgiveness. Instead of wiping out debts, it seeks to prevent future mistakes by educating borrowers and tightening servicer accountability. Yet both approaches accept the premise that the federal government should remain the primary financier of higher education. Whether through forgiveness on the back end or counseling on the front end, Washington remains deeply enmeshed in a system that is failing students and taxpayers alike.

This bipartisan reluctance to confront the root problem reflects the political economy of higher education. Universities depend on federal aid for revenue. Students and parents view loans as a necessary ticket to middle-class status. Politicians are reluctant to challenge either group. As a result, reforms gravitate toward the margins, improving communication, tweaking servicing, and adjusting repayment formulas while the underlying incentives remain untouched. The new ombudsman’s office is merely the latest example.

Proposed Changes Are Marginally Beneficial But Won’t Solve the Debt Crisis

The Department of Education is right to acknowledge the confusion and inconsistency that plague federal student-loan servicing. Expanding the ombudsman’s role into consumer education and creating a new common manual may reduce frustration, standardize practices, and help some families make more informed choices. But these reforms should not be mistaken for a solution to the student-debt crisis. The crisis is structural, not informational. It stems from a federal loan program that encourages overborrowing, inflates tuition, and misaligns education with the labor market.

Policymakers must resist the temptation to declare victory once the ombudsman’s office has been repurposed and a new manual published. Without deeper reforms—reducing federal loan availability, expanding alternatives to debt, and holding institutions accountable for outcomes—borrowers will continue to struggle, defaults will persist, and taxpayers will remain on the hook. Consumer education can inform families, but only structural change can fix the system. Until then, the federal government’s well-meaning efforts will amount to little more than rearranging the deck chairs on a ship taking on water.

Jack Salmon is a research fellow and Gibbs scholar at the Mercatus Center and was previously the director of policy research at Philanthropy Roundtable. His work has been featured in a variety of outlets, including The Hill, Business Insider, RealClearPolicy, and National Review.